29 May 2010

Meditation science

http://www.marc.ucla.edu/index.php?option=com_frontpage&Itemid=1

Physiological effects of meditation

http://www.noetic.org/research/medbiblio/index.htm

http://natural-meditation.org/ResearchedEffects.htm

Control over body temperature

http://www.hno.harvard.edu/gazette/2002/04.18/09-tummo.html

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tummo

28 May 2010

Aerobic exercise: More pain now for less later

Link

Q: What else can someone do to relieve pain besides take a prescription pain reliever or undergo a procedure?

A: There are so many self-help things you can do. Something as simple as trying to do 30 minutes of aerobic exercise can help. With pain, you’re in a vicious cycle – you take more narcotics, your REM sleep decreases, and then you’re tired and you don’t want to exercise. If you can get through the first week or two of extra pain by doing the proper exercise, like 30 minutes of walking daily, long term that’s going to have an impact. Most people give up on simple walking, but it can have a huge impact long term.

Q: For people treating pain with exercise, do you have to be willing to get worse in order to get rid of pain eventually?

A: In the case of exercises, that’s true. If the pain goes up four-fold, you’re doing something wrong, but proper exercise will make you a little worse for a while before it makes you better. It’s a pain desensitization period. Think about if you have raw skin on your knuckle and you tap it. At first it hurts, but if you tap it more and more it will get desensitized. You’re doing the same to your chronic pain structure when you exercise. There is so much data on this with rehabilitation for back pain, for instance. You become pain desensitized by proper exercise with gradual increases in stress. The overall consensus for exercise therapy is that it has a positive impact. It can be something simple — it doesn’t have to be fancy machines or stretches.

19 May 2010

Torture's effect on society

http://nationaljournal.com/about/njweekly/stories/2005/1119nj1.htm#

13 May 2010

Heat therapy for abdominal pain

ScienceDaily (Jul. 5, 2006)The old wives’ tale that heat relieves abdominal pain, such as colic or menstrual pain, has been scientifically proven by a UCL (University

College London) scientist, who will present the findings today at the

Physiological Society’s annual conference hosted by UCL.

Dr Brian King, of the UCL Department of Physiology, led the research

that found the molecular basis for the long-standing theory that heat,

such as that from a hot-water bottle applied to the skin, provides

relief from internal pains, such as stomach aches, for up to an hour.

Dr King said: “The pain of colic, cystitis and period pain is caused

by a temporary reduction in blood flow to or over-distension of hollow

organs such as the bowel or uterus, causing local tissue damage and

activating pain receptors.

“The heat doesn’t just provide comfort and have a placebo effect –

it actually deactivates the pain at a molecular level in much the same

way as pharmaceutical painkillers work. We have discovered how this

molecular process works.”

If heat over 40 degrees Celsius is applied to the skin near to where

internal pain is felt, it switches on heat receptors located at the

site of injury. These heat receptors in turn block the effect of

chemical messengers that cause pain to be detected by the body.

The team found that the heat receptor, known as TRPV1, can block

P2X3 pain receptors. These pain receptors are activated by ATP, the

body’s source of energy, when it is released from damaged and dying

cells. By blocking the pain receptors, TRPV1 is able to stop the pain

being sensed by the body.

Dr King added: “The problem with heat is that it can only provide

temporary relief. The focus of future research will continue to be the

discovery and development of pain relief drugs that will block P2X3

pain receptors. Our research adds to a body of work showing that P2X3

receptors are key to the development of drugs that will alleviate

debilitating internal pain.”

Scientists made this discovery using recombinant DNA technology to

make both heat and pain receptor proteins in the same host cell and

watching the molecular interactions between the TRPV1 protein and the

P2X3 protein, switched on by capsaicin, the active ingredient in

chilli, and ATP, respectively.

Adapted from materials provided by University College London.

University College London (2006, July 5). Heat Halts Pain Inside The Body. ScienceDaily. Retrieved March 19, 2008, from http://www.sciencedaily.com /releases/2006/07/060705090603.htm

11 May 2010

Carnival

http://www.howtocopewithpain.org/blog/2361/pain-blog-carnival-april-2010/

Definitely check it out.

Contest!

The contest details are here:

http://www.howtocopewithpain.org/blog/2287/contest-write-a-guest-article/

The deadline is 16th May, so hurry......

29 April 2010

Aquinas on privation

As was said above (A[1]), evil imports the absence of good. But not every absence of good is evil. For absence of good can be taken in a privative and in a negative sense. Absence of good, taken negatively, is not evil; otherwise, it would follow that what does not exist is evil, and also that everything would be evil, through not having the good belonging to something else; for instance, a man would be evil who had not the swiftness of the roe, or the strength of a lion. But the absence of good, taken in a privative sense, is an evil; as, for instance, the privation of sight is called blindness. Now, the subject of privation and of form is one and the same---viz. being in potentiality, whether it be being in absolute potentiality, as primary matter, which is the subject of the substantial form, and of privation of the opposite form; or whether it be being in relative potentiality, and absolute actuality, as in the case of a transparent body, which is the subject both of darkness and light. It is, however, manifest that the form which makes a thing actual is a perfection and a good; and thus every actual being is a good; and likewise every potential being, as such, is a good, as having a relation to good. For as it has being in potentiality, so has it goodness in potentiality. Therefore, the subject of evil is good.

08 April 2010

NY Times Patient Voices series

Here're some of the pain related ones:

Patient Voices: Rheumatoid Arthritis

01 April 2010

Review of David Biro's The Language of Pain

Short story: David Biro's The Language of Pain: Finding Words, Compassion and Relief is very good.

Go buy it.

Longer story: The publisher sent me an advance copy of Biro's The Language of Pain a few months ago. I've read it several times and been working on a review to share with y'all. But the review is getting too long and though I think I agree with most of his conclusions, I'm still not entirely sure what I think about about several of his arguments. Nonetheless, I've certainly profited from engaging with them.

Thus in the interest of posting something while the book is still (somewhat) fresh, I've pasted some of the early parts of the review below. I may post the rest later, or I may work it into something for a more formal venue. I'm omitting the philosophical discussion of the arguments. Though I will list a couple of the topics that concern me. I'm sure the list won't make sense until you've read the book. But perhaps they'll serve as discussion-starters

----

Those interested in learning about pain can profit from David Biro’s The Language of Pain: Finding Words, Compassion and Relief. It will probably be the most useful to people with chronic pain and those close to them. At the very least, the vast array of nuanced metaphors and literary sources he canvases can serve as raw material for their attempts to communicate and understand the experience of pain. But I expect that his lucid exploration of the structure of these metaphors will provide important conceptual tools for crafting more systematic and effective narratives. Though the applicability of some of his particular insights may be limited by culture and language.

Clinicians and scientists should be impressed by the conceptual structure that Biro uncovers in the language many sufferer's use to describe their pains. He succeeds in showing that this metaphorical talk, while necessarily imprecise and often obscure, must be taken seriously. In his wake, the same cannot be said for those who dismiss or deride these ways of talking about pain.

At a minimum, researchers interested in developing pain measurement tools and many philosophers will find in it a rich repository of examples and ideas to use in their work.

Philosophers should also find much to be intrigued by in Biro’s arguments. Here are a few of points that I think are worth engaging with:

- Chapter 2 is occupied with a theoretical response to the charge that pain is completely resistant to language. This is unnecessary. The main thrust of the book is an empirical argument that, in several important ways, pain is in fact amenable to language.

- The Wittgensteinian argument of chapter 2 can at best show that we must be able to communicate that we are in pain. But his project is to show that we can communicate what it is like to be in pain. He's not confusing the two in chapter 2. He wants to use the former as a wedge to open the door for the latter. But later on they sometimes seem to get run together in significant ways.

- His discussion of the language/metaphors of agency does a lot to support and build on Elaine Scarry's articulation of the concept (I profited a great deal from this part since the pain-agency connection is important in my own work). The discussions of the x-ray and mirror metaphors/language are much weaker. Indeed, I'm not convinced that these can't be folded into the agency metaphor. [Unlike the others, this concern has significant philosophical consequences for our understanding of pain]

- I'm probably being overly picky --but, hey, that's what analytic philosophers are for-- but his project is about language (hence the title and the claim to be constructing a 'rhetoric'). I usually think of language as propositional. His discussions using art to express pain thus seem incongruous. This is probably innocuous. At most it's a concern about whether the thesis should be framed in terms of language or more broadly in terms of our ability to meaningfully communicate. Though I sometimes think that there may be something lurking here that's related to the more substantive questions about whether the x-ray and mirror metaphors are really separate from the agency metaphors.

- I'm betting that analytic philosophers of language who work on metaphor will find a great deal to disagree with in some of his arguments. Though I myself don't know enough about these issues to have more than hazy suspicions at various points.

Like I said, I'm not entirely sure what I think about these and other points. But I've certainly profited from thinking about them. And in any event, none of them undermine the practical import of the book or the philosophical suggestiveness of the overall picture. Indeed, his subtle discussions of pain language’s structure do not require the conceptually strong thesis that the experience of pain is necessarily expressible. By weaving together art, literature, personal experience, and patient testimony, he has demonstrated that many aspects of many pain experiences can, to a practically useful degree, be meaningfully shared.

A critique and new version of the Wong-Baker Pain Faces Scale

We're all familiar with the Wong-Baker Pain Faces Scale.

But as our Hyperbolic critic notes, this is easily misunderstood. For example, she interprets it as

0: Haha! I'm not wearing any pants!

2: Awesome! Someone just offered me a free hot dog!

4: Huh. I never knew that about giraffes.

6: I'm sorry about your cat, but can we talk about something else now? I'm bored.

8: The ice cream I bought barely has any cookie dough chunks in it. This is not what I expected and I am disappointed.

10: You hurt my feelings and now I'm crying!

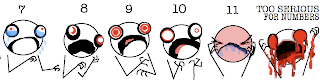

Thus she has come up with a better scale:

Which she interprets as:

0: Hi. I am not experiencing any pain at all. I don't know why I'm even here.

1: I am completely unsure whether I am experiencing pain or itching or maybe I just have a bad taste in my mouth.

2: I probably just need a Band Aid.

3: This is distressing. I don't want this to be happening to me at all.

4: My pain is not fucking around.

5: Why is this happening to me??

6: Ow. Okay, my pain is super legit now.

7: I see Jesus coming for me and I'm scared.

8: I am experiencing a disturbing amount of pain. I might actually be dying. Please help.

9: I am almost definitely dying.

10: I am actively being mauled by a bear.

11: Blood is going to explode out of my face at any moment.

Too Serious For Numbers: You probably have ebola. It appears that you may also be suffering from Stigmata and/or pinkeye.

I expect to see this written up in Pain shortly.

14 March 2010

Mutations in the SCN9A gene and pain sensitivity

Gene Linked To Pain Perception - Science News: "Gene linked to pain perception

Common genetic variant makes some people more sensitive

By Laura Sanders

Web edition : Monday, March 8th, 2010

[....]

The team found that people who reported higher levels of pain were more likely to carry a particular DNA base, an A instead of a G, at a certain location in the gene SCN9A. The A version is found in an estimated 10 to 30 percent of people, Woods says, though its presence varies in populations of different ancestries.

[....]

The same trend — higher pain levels reported by people who carried the A — held true in cohorts of people with other painful conditions including sciatica, phantom limb syndrome and lumbar discectomy.

[....]

The genetic variation affects the structure of a protein that sits on the outside of nerve cells and allows sodium to enter upon painful stimuli. The sodium influx then spurs the nerve cell to send a pain message to the brain.

This channel protein is a promising target for extremely specific and effective pain drugs, Waxman says: ‘Given that this channel has been indicted, it would be nice if we could develop therapeutic handles that turn it off or down.’

Researchers already knew that people with mutations in SCN9A can have extreme pain syndromes. Genetic changes that render the protein completely inactive can leave a person impervious to pain, although otherwise healthy. Other mutations can lead to conditions such as ‘man on fire’ syndrome, in which people experience relentless, searing pain.

[....]

In additional laboratory studies, the researchers found that nerve cells carrying the A variant of the gene took longer to close their sodium gates, allowing a stronger pain signal to be sent to the brain. Nerve cells carrying the more common G version of the gene snapped shut faster, stopping the pain signal sooner. "

19 February 2010

Placebo effect video

Also, the point at the end about using the research on placebos is bolstered by research on the nocebo effect -where contextual cues make the condition worse (though the nocebo effect lacks much of the placebo effect's nuance).

17 February 2010

My mom must be proud

Do opiates decrease telepathic abilities?I hope the 5 people arriving from 3 different countries found the answers they were looking for.

15 February 2010

Fetal pain

(1) Is the neurophysiology upon which pain-involving mental states supervene present in fetuses of x weeks?and

(2) Is fetal pain --if it exists-- bad for the fetus?Here's two reasons for thinking they come apart.

First, it's worth remembering that the aversiveness of pain is to some extent learned (see, for example, the famous McGill dog study). It might be that there is a pain sensation, but that the fetus has not learned to experience it as something bad. There might be evidence for or against this. But it probably wouldn't come from the fetus exhibiting near-reflex escape behaviors. IIRC, in adults many such behaviors are triggered very early in pain processing, even before much of the emotional processing occurs.

Second, there's the very hard question of whether fetuses are yet the sort of creatures that can have things be bad for them. Though I'm obsessed with the general problem (what makes something the subject of agent-relative value) I won't even try to articulate this one here. Especially because it actually a complex of several different super-hard issues.

Omaha.com - The Omaha World-Herald: Metro/Region - When can fetus feel pain?: "Knowing when a fetus first feels pain is like many scientific endeavors: It involves speculation and disagreement.

A bill before the Nebraska Legislature, the Abortion Pain Prevention Act, would ban abortions 20 weeks after conception, because it's at that point, Speaker of the Legislature Mike Flood says, that a fetus begins to sense pain.

‘The science is compelling,’ the Norfolk lawmaker wrote on his Web site about the bill that is scheduled for a hearing Feb. 25.

In fact, there still is considerable disagreement among scientists, physicians and other experts. It's fairly common for a person's position on the question to mirror his position on abortion. But it's not clear when the complex communication circuitry in the body, spine and brain are developed enough for pain to be felt.

Nerve fibers designed to sense pain are present in a fetus's skin seven or eight weeks after conception, said Dr. Terence Zach, chairman of pediatrics at the Creighton University School of Medicine.

Surely by 20 weeks, Zach said, a fetus is mature enough to respond to what scientists call ‘noxious stimuli,’ or pain.

‘I believe that — yep,’ said Zach, who described himself as pro-life.

Another Omaha physician, Dr. Robert Bonebrake, agrees with Zach. Bonebrake, a perinatologist at Methodist Hospital, sometimes must give blood transfusions to fetuses or drain fluid from them at 21 or 22 weeks.

Those procedures involve inserting a needle or shunt into the fetus. Bonebrake said the fetus will ‘back away a little bit’ from the needle, indicating to him that it has felt the jab.

‘He or she will try to move away if possible,’ said Bonebrake, who also described himself as pro-life.

But in a review of fetal pain literature, University of California-San Francisco physicians reported in 2005 that ‘fetal perception of pain is unlikely before the third trimester,’ or about 27 weeks into the pregnancy.

The review, published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, said reflex movement isn't proof of pain, because it can occur without the brain being developed enough for conscious pain recognition.

The article also stated that only 1.4 percent of abortions in the U.S. occur at or after 21 weeks.

In Nebraska, fetal age doesn't have to be reported and usually isn't, according to a state health spokeswoman. But in cases where it was reported, none of the abortions that occurred in Nebraska in 2008 involved fetuses of 20 weeks or older.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists' position is that it ‘knows of no legitimate scientific information that supports the statement that a fetus experiences pain at 20 weeks' gestation.’

A Children's Hospital Boston anesthesiologist and researcher, Dr. Roland Brusseau, has studied the subject to determine whether a fetus undergoing a surgical procedure should have anesthesia. His institution is the main children's hospital of Harvard Medical School.

Brusseau calls discussions of fetal pain ‘complicated and controversial.’

He has suggested a broad timeline for when fetal pain might start: ‘If we are to accept that consciousness is possible by 20 weeks (or more conservatively, 30 weeks), then it also would appear possible that fetuses could experience something approximating ‘pain,'’ he wrote a little more than three years ago.

The possibility, he said, would appear to mandate the use of appropriate anesthesia when performing fetal surgery.

Federal legislation has been unsuccessfully introduced over the past several years to require abortion providers to inform the mother that the fetus could feel pain at 20 weeks and offer anesthesia directly to the fetus.

Six states — Oklahoma, Arkansas, Utah, Georgia, Louisiana and Minnesota — have passed similar legislation, according to the Center for Reproductive Rights in New York.

In Iowa, a bill to that effect in the Legislature failed in 2005.

What makes Flood's legislation different is that its answer to the question of fetal pain is to ban abortions after 20 weeks. Exceptions would be allowed if an abortion is deemed necessary to avoid substantial harm or death to the mother.

Flood said that laws protect animals in slaughterhouses from excessive pain, and that fetuses deserve that level of sensitivity.

He said he based his beliefs that fetuses feel pain at 20 weeks in part on assertions by Drs. Jean Wright and K.J.S. ‘Sunny’ Anand. Wright is former chairwoman of pediatrics at Mercer University School of Medicine's Savannah, Ga., campus and Anand is chief of pediatric critical care at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center.

Flood said experts have found, for instance, that stress hormones spike when fetuses undergo invasive procedures.

Wright couldn't be reached for comment, but Anand, who was reached while doing humanitarian work in Haiti, said fetuses show signs of sensory perception around 20 weeks.

‘Whether this happens at 20 weeks or 22 weeks or 18 weeks is still open to question,’ Anand said. Some fetuses might develop more quickly than others, he said.

Anand said he believes the sense of pain in a fetus isn't turned on like a light switch. ‘It's more like a dimmer switch that very slowly — very, very gradually — turns on particular sensory modalities.’

Anand said the chain of connections for pain perception includes nerve fibers, spinal cord circuitry, brain stem and other portions of the brain. It's impossible to know for sure whether a fetus feels pain, he said.

But denying there is pain, he said, means there's no incentive to study it, no reason to work out ways to anesthetize fetuses, and no need for a doctor to consider whether pain is being inflicted.

‘But I think the onus is on us to give the benefit of the doubt,’ he said.

Anand said he believes abortion is appropriate in some instances, such as if a teenager has been raped, and inappropriate in others, such as when a woman has broken up with a boyfriend and then learns she's pregnant.

Arthur Caplan, professor of medical ethics and director of the Center for Bioethics at the University of Pennsylvania, said that ‘on the whole, I don't think science and medicine can be drawn in to support’ Flood's bill.

Caplan, who has a doctorate in philosophy, called himself ‘a conservative pro-choicer.’ He said that there is no consensus among physicians and scientists on the subject of fetal pain and that the notion that pain is felt at 20 weeks is ‘not the mainstream opinion.’

Bellevue abortion provider Dr. LeRoy Carhart, who has said he will perform late-term abortions only in cases when the fetus can't survive outside the womb, said he doesn't believe there is fetal pain before or during his abortions.

Nevertheless, Carhart said when performing abortions in cases where the fetus is 17 weeks or older, he sedates the mother — which sedates the fetus — and then administers another injection to stop the fetus's heart. The abortion typically occurs 24 to 72 hours later, he said.

‘This should be the ‘Put Carhart Out of Business Bill,'’ he said of Legislative Bill 1103.

Flood denied that his bill was directed at Carhart's revenue and said: ‘Dr. Carhart's loss of business pales in comparison to the loss of young lives.’

Dr. Michael Barsoom, director of maternal-fetal medicine at the Creighton School of Medicine, said he has seen fetuses move away from needles when needles are put in or near them.

Whether that's a reaction to pain, though, is unclear, Barsoom said. The fetus might respond reflexively and not as a conscious pain experience, he said.

‘I honestly don't know,’ said Barsoom, who described himself as pro-life. He said he doesn't think anyone can say for sure when a fetus begins to feel pain.

‘I don't think there's any way to find out.’"

Oklahoma restricting injections for chronic pain

Oklahoma House gets bill restricting injections for chronic pain | NewsOK.com: "

Only physicians would be allowed to administer precise pain management injections under a bill approved Tuesday by a House committee.

The House Public Health Committee approved Senate Bill 1133 by a 14-5 vote. It now goes to the full House.

Rep. John Trebilcock, who took over authorship of the bill, said pain management injections into a patient’s spinal or neck area must be precisely administered.

'Chronic pain medication is medicine and should be practiced by doctors,’ said Trebilcock, R-Broken Arrow.

The measure was carried over from last year after it failed to win passage. Efforts to come up with a compromise among a hospital group, doctors and certified registered nurse anesthetists fizzled. Certified registered nurse anesthetists now administer spinal injections to manage pain.

Trebilcock said the practice of chronic pain management is 'extremely dangerous.’

An injection in the wrong spot could cause paralysis or not effectively treat the pain, he said.

Trebilcock said certified nurse anesthetists would be allowed to continue to give other injections. It’s estimated the chronic pain injections take up only about 4 percent of their duties, he said.

Marvin York, a lobbyist for the Oklahoma Association of Nurse Anesthetists, said the measure would be a hardship to rural patients, because few rural doctors practice in pain management.

'I can’t imagine why any rural legislator ... could possibly be for this bill,’ he said.

Victor Long of Norman, a certified registered nurse anesthetist, said about 80 percent of the spinal injections for pain are administered by certified registered nurse anesthetists. About 500 certified registered nurse anesthetists are in the state, he said.

Rep. Pat Ownbey, R-Ardmore, said he wondered why the bill was necessary because no complaints had been filed against certified registered nurse anesthetists administering chronic pain management injections.

'Is this a patient issue or a money issue?’ he asked fellow committee members. 'Make no mistake, this is a turf war.’

Trebilcock said doctors are willing to travel to rural areas to administer the injections.

'Rural Oklahoma shouldn’t have to settle for less than a doctor when they suffer from chronic pain,’ he said."

14 February 2010

Healthcare-Associated Infection

The Kimberly-Clark Health Care Company has an informational (and of course promotional) website on healthcare associated infections here Patients who want to get a sense of the problem and what they should keep an eye out for may find some of the links useful.

06 February 2010

Anguish

[a. OFr. anguisse, angoisse (Pr. angoissa, It. angoscia) the painful sensation of choking:{em}L. angustia straitness, tightness, pl. straits, f. angust-us narrow, tight, f. root angu- in ang(u)-{ebreve}re to squeeze, strangle, cogn. w. Gr. {alenisacu}{gamma}{chi}-{epsilon}{iota}{nu}.]

Formerly with pl.

1. Excruciating or oppressive bodily pain or suffering, such as the sufferer writhes under.

c1220 Hali Meid. 35 Hwen hit {th}er to cume{edh} {th}at sar sorhfule angoise. a1300 Pop. Sc. (Wright) 374 The bodi..in strong angusse doth smurte. c1380 Sir Ferumb. 212 Hys wounde..for angwys gan to chyne. 1382 WYCLIF Jer. iv. 31 Anguysshes as of the child berere [1388 angwischis as of a womman childynge; 1611 the anguish as of her that bringeth forth her first child]. c1386 CHAUCER Pars. T. 139 The peyne of helle..is lik deth, for the horrible anguisshe [v.r. angwissh(e, -uysch, -uyssche, -wysshe]. 1485 CAXTON Chas. Gt. 238, I haue suffred many anguysshes of hungre. 1592 SHAKES. Rom. & Jul. I. ii. 47 One paine is lesned by anothers anguish. 1656 RIDGLEY Pract. Physick 150 If there be pain of the Stomach, anguish, heat. 1758 S. HAYWARD Serm. xvii. 520 His [Job's] body was full of anguish. 1880 CYPLES Hum. Exp. iii. 70 The anguish of corns and toothache.

2. Severe mental suffering, excruciating or oppressive grief or distress.

c1230 Ancr. R. 234 In the muchel anguise aros {th}e muchele mede. 1297 R. GLOUC. 177 In gret anguysse and fere Wepynde byuore {th}e kyng. c1325 E.E. Allit. P. C. 325 When {th}acces of anguych wat{ygh} hid in my sawle. 1382 WYCLIF Prov. xxi. 23 Who kepeth his mouth and his tunge, kepeth his soule fro anguysschis. c1450 Merlin 64 Grete angwysshe that he suffred for the love of Ygerne. 1583 STANYHURST Aeneis II. (Arb.) 46 With choloricque fretting I dumpt, and ranckled in anguish. 1611 BIBLE Job vii. 11, I wil speake in the anguish of my spirit. 1678 JENKINS in Pepys VI. 125 An honest man..full of Anguishes for his King and his Country. 1769 Junius Lett. xxiii. 105 You may see with anguish how much..authority you have lost. 1810 SCOTT Lady of L. II. xxxiv, The deep anguish of despair.

25 January 2010

Man experiences intense pain from nail that slid between his toes Boing Boing

Man experiences intense pain from nail that slid between his toes Boing Boing: ""

Mind Hacks reports that a nail penetrated the shoe of a 29-year-old construction worker, causing great pain. But the hospital workers discovered that the nail had passed harmlessly between his toes.

A builder aged 29 came to the accident and emergency department having jumped down on to a 15 cm nail. As the smallest movement of the nail was painful he was sedated with fentanyl and midazolam. The nail was then pulled out from below. When his boot was removed a miraculous cure appeared to have taken place. Despite entering proximal to the steel toecap the nail had penetrated between the toes: the foot was entirely uninjured.

Mind Hacks says this is related to "somatisation disorder, where physical symptoms appear that aren't explained by tissue damage."

H/T: Saba

Does Morphine Stimulate Cancer Growth?

GeriPal does yeoman's work in explaining why

Does Morphine Stimulate Cancer Growth? | GeriPal - A Geriatrics and Palliative Care Blog: ""

31 December 2009

TENS confusion

Widely used device for pain therapy not recommended for chronic low back pain A new guideline issued by the American Academy of Neurology finds that transcutaneous electric nerve stimulation (TENS), a widely used pain therapy involving a portable device, is not recommended to treat chronic low-back pain that has persisted for three months or longer because research shows it is not effective.... TENS can be effective in treating diabetic nerve pain, also called diabetic neuropathy, but more and better research is needed to compare TENS to other treatments for this type of pain. Research on TENS for chronic low-back pain has produced conflicting results. For the guideline, the authors reviewed all of the evidence for low-back pain lasting three months or longer. Acute low-back pain was not studied. The studies to date show that TENS does not help with chronic low-back pain.So far so good. But then in the nickel summary of what TENS is they write:

With TENS, a portable, pocket-sized unit applies a mild electrical current to the nerves through electrodes. TENS has been used for pain relief in various disorders for years. Researchers do not know how TENS may provide relief for pain. One theory is that nerves can only carry one signal at a time. The TENS stimulation may confuse the brain and block the real pain signal from getting through.

How about:

Neural signals reporting injury have to pass through a gate in the spine in order to be transmitted to the brain and cause pain. The electric impulse from TENS closes the gate.

That's still inaccurate. But it at least avoids framing the phenomenon as the system stopping the pain before it gets to the brain. Getting people used to distinguishing between nociception and pain is a small but important step in a better public understanding of analgesia and chronic pain conditions.

11 December 2009

Acetaminophen-Related Liver Damage May Be Prevented By Common Herbal Medicine

Acetaminophen-Related Liver Damage May Be Prevented By Common Herbal Medicine: "Acetaminophen-Related Liver Damage May Be Prevented By Common Herbal Medicine

A well-known Eastern medicine supplement may help avoid the most common cause of liver transplantation, according to a study by researchers at the Stanford University School of Medicine. The finding came as a surprise to the scientists, who used a number of advanced genetic and genomic techniques in mice to identify a molecular pathway that counters acetaminophen toxicity, which leads to liver failure.

'I didn't know anything about the substance that was necessary for the pathway's function, so I had to look it up,' said Gary Peltz, MD, PhD, professor of anesthesiology. 'My postdoctoral fellow, whose parents and other family members in Asia were taking this compound in their supplements, started laughing. He recognized it immediately.'

The molecule was S-methylmethionine, which had been marketed as an herbal medicine known as Vitamin U for treatment of the digestive system. It is highly abundant in many plants, including cabbage and wheat, and is routinely ingested by people. [...]

Peltz is the senior author of the research, which will be published online Nov. 18 in Genome Research. The experiments were conducted in Peltz's laboratory at Roche Palo Alto in Palo Alto, Calif., where Peltz worked before coming to Stanford in July 2008. He is continuing the research at Stanford. The first author of the paper, Hong-Hsing Liu, MD, PhD, is now a postdoctoral scholar in Peltz's Stanford lab.

Acetaminophen is a pain reliever present in many over-the-counter cold and flu medicines. It is broken down, or metabolized, in the body into byproducts - one of which can be very toxic to the liver. At normal, therapeutic levels, this byproduct is easily deactivated when it binds to a naturally occurring, protective molecule called glutathione. But the body's glutathione stores are finite, and are quickly depleted when the recommended doses of acetaminophen are exceeded.

Unfortunately, the prevalence of acetaminophen makes it easy to accidentally exceed the recommended levels, which can occur by dosing more frequently than indicated or by combining two or more acetaminophen-containing products. However, severe liver damage can occur at even two to three times the recommended dose (the maximum adult dose is 4 grams per day; toxic daily levels range from 7 to 10 grams).

'It's a huge public health problem,' said Peltz. 'It's particularly difficult for parents, who may not realize that acetaminophen is in so many pediatric medicines.' Acetaminophen overdose is the most common cause of liver transplantation in this country. The only effective antidote is an unpalatable compound called NAC that can induce nausea and vomiting, and must be administered as soon as possible after the overdose.

Peltz and his colleagues used 16 inbred strains of laboratory mice for their investigations. Most strains are susceptible to acetaminophen toxicity, but one is resistant. They compared how the drug is metabolized by the different strains and looked for variations in gene expression and changes in endogenous metabolites in response to acetaminophen administration. They identified 224 candidate genes that might explain the resistant strain's ability to ward off liver damage, and then plumbed computer databases to identify those involved in metabolizing acetaminophen's dangerous byproducts.

One, an enzyme called Bhmt2, fit the bill: It helped generate more glutathione, and its sequence varied between the resistant and non-resistant strains of mice. Bhmt2 works by converting the diet-derived molecule S-methylmethionine, or SMM, into methionine, which is subsequently converted in a series of steps into glutathione. The researchers confirmed the importance of the pathway by showing that SMM conferred protection against acetaminophen-induced liver toxicity only in strains of mice in which the Bhmt2 pathway was functional.

'By administering SMM, which is found in every flowering plant and vegetable, we were able to prevent a lot of the drug's toxic effect,' said Peltz. He and his colleagues are now working to set up clinical trials at Stanford to see whether it will have a similar effect in humans. In the meantime, though, he cautions against assuming that dosing oneself with SMM will protect against acetaminophen overdose.

'There are many pathways involved in the metabolism of this drug, and individuals' genetic backgrounds are tremendously variable. This is just one piece of the puzzle; we don't have the full answer,' he said. However, if subsequent studies are promising, Peltz envisions possibly a co-formulated drug containing both acetaminophen and SMM or using SMM as a routine dietary supplement."

*I don't doubt its usefulness for many conditions. What I don't like is how it's seen/promoted/prescribed as something benign by consumers/companies and drug stores/doctors.

Antidepressants, CYP2D6, and opioid metabolism

Take it away, Peter:

[Usual disclaimer: Neither he nor I are medical professionals. Don't take this as medical advice, et cetera.]

Since emailing you I’ve been studying the research literature and it’s crystal clear that codeine will not have any analgesic properties for people either genetically lacking CYP2D6 (6-10% of caucasians, other %’s for other ethnic groups) or who are taking a drug that blocks it.

Many antidepressants, including fluoxetine, paroxetine and bupropion are strong inhibitors of it, as are many other drugs including various antiarrhythmics, antifungals, cancer drugs, etc.

The story on the other synthetic opioids doesn’t look too good either. CYP2D6 plays a critical role in the metabolism of hydrocodone, oxycodone, and tramadol but they have more complex metabolic pathways and even now there are details that remain to be elucidated.

Hydrocodone itself has little affinity for the μ opioid (pain) receptors so it has to get metabolized the main clinically-active metabolite is assumed to be hydromorphone because it’s a known painkiller with a high affinity for the μ opioid receptors. And lack of CYP2D6 blocks that process. That part is clear, but there are unanswered questions.

For example in Kaplan et al, (Inhibition of cytochrome P450 2D6 metabolism of hydrocodone to hydromorphone does not importantly affect abuse liability J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997 Apr;281(1):103-8) subjects’ subjective perception of the effects of hydrocodone were unrelated to hydromorphone conversion. Heiskanen et al, (Effects of blocking CYP2D6 on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of oxycodone. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1998 Dec;64(6):603-11. ) performed a similar experiment involving oxycodone with similar results.

But critically, neither experiment looked at pain tolerance. Also Otton et al, (CYP2D6 phenotype determines the metabolic conversion of hydrocodone to hydromorphone - SV - Clin Pharmacol Ther - 01-NOV-1993; 54(5):) performed an experiment similar to Kaplan’s but did find that subjects responded in ways consisten with hydromorphone conversion (again, no pain test).

Based on what we think we know about hydrocodone (i.e., that the active metabolite is hydromorphone), Otton’s results make more sense. But both hydrocodone and oxycodone still have work left to do elucidating the effects of some of the other metabolites that are currently thought to be inactive.

And Heiskanen’s results also make sense because oxycodone – the parent compound - actually appears to have a nontrivial affinity for μ receptors itself, and furthermore some of its other metabolites such as noroxycodone, which may be mediated by a different enzyme – CYP2C19 - may also have high binding affinity. (Lalovic et al, Quantitative contribution of CYP2D6 and CYP3A to oxycodone metabolism in human liver and intestinal microsomes. Drug Metab Dispos. 2004 Apr;32(4):447-54. )

In other words oxycodone may work fine as an analgesic for CYP2D6 impaired patients. BUT that doesn’t mean oxycodone gets us off the hook - instead it appears to have a nastier hook: The oxymorhone is far more readily cleared than the parent compound oxycodone. So without CYP2D6 oxycodone accumulates, potentially becoming toxic or fatal.

Two studies underscore that risk: Jannetto, et al, Pharmacogenomics as molecular autopsy for postmortem forensic toxicology; genotyping cytochrome P450 2D6 for oxycodone cases. J Anal Toxicol 2002; 26:438–447 and Drummer et al, A study of deaths involving oxycodone. J Forensic Sci 1994; 39:1069–1075.

The real bottom lines are these:

1. Work remains to be done in elucidating both the pharmacokinetics and clinical effects of various metabolites for all of the synthetic opioids.

2. As far as I could tell, there seem to be no human studies evaluating analgesic properties of synthetic opioids for patients who either lack the gene for CYP2D6 or for whom CYP2D6 is blocked by a drug-drug interaction.

3. Drug-drug interactions of this type will become more common as the population becomes older and as we use a greater variety of drugs. As it is, bupropion. paroxetine and fluoxetine (all potent CYP2D6 blockers) accounted for roughly 50 million prescriptions in the US alone last year. Other CYP2D6 blockers account for millions more.

4. I’ve spoken to several physicians about this and they all expressed worry and concern that they feel unsure how to do pain management for CYP2D6-impaired patients, especially in postoperative or fracture cases where OTC drugs aren’t enough and the “nuclear options” like fentanyl or methadone (both of which work regardless of CYP2D6) would be overkill and dangerous.

Visit Peter's blog at http://blog.pnart.com/. Thanks again!

12 November 2009

What's bad about masochistic pain?

http://www.adamswenson.net/HSG/HSG1.htmlBut since it's just me reading the paper aloud, you'll probably want to skip ahead and just watch the discussion:

Part 1 http://www.adamswenson.net/HSG/HSG2.htmlThe paper and powerpoint slides are available on the website.

Part 2 http://www.adamswenson.net/HSG/HSG3.html

Warning: This is totally unsafe for work, and most definitely not for the squeamish. The talk proper may cause mild reactions in those allergic to analytic philosophy. Such reactions are less common with the discussion alone.

08 November 2009

Children Can Greatly Reduce Abdominal Pain By Using Their Imagination: UNC Study

Children Can Greatly Reduce Abdominal Pain By Using Their Imagination: UNC Study: "

Children with functional abdominal pain who used audio recordings of guided imagery at home in addition to standard medical treatment were almost three times as likely to improve their pain problem, compared to children who received standard treatment alone.

And those benefits were maintained six months after treatment ended

[....]

The study focused on functional abdominal pain, defined as persistent pain with no identifiable underlying disease that interferes with activities. It is very common, affecting up to 20 percent of children. Prior studies have found that behavioral therapy and guided imagery (a treatment method similar to self-hypnosis) are effective, when combined with regular medical care, to reduce pain and improve quality of life.

[....]

In the group that used guided imagery, the children reported that the CDs were easy and enjoyable to use. In that group, 73.3 percent reported that their abdominal pain was reduced by half or more by the end of the treatment course. Only 26.7 percent in the standard medical care only group achieved the same level of improvement. This increased to 58.3 percent when guided imagery treatment was offered later to the standard medical care only group. In both groups combined, these benefits persisted for six months in 62.5 percent of the children.

"

Acetaminophen May Be Linked To Asthma In Children And Adults

Acetaminophen May Be Linked To Asthma In Children And Adults: "New research shows that the widely used pain reliever acetaminophen may be associated with an increased risk of asthma and wheezing in both children and adults exposed to the drug. Researchers from the University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada, conducted a systematic review and metaanalysis of 19 clinical studies (total subjects=425,140) that compared the risk of asthma or wheezing with acetaminophen exposure.

The analysis showed that the pooled odds ratio (odds ratio for all studies combined) for asthma among users of acetaminophen was 1.63. The risk of asthma in children who used acetaminophen in the year prior to asthma diagnosis or in the first year of life was elevated to 1.60 and 1.47, respectively.

Furthermore, results showed a slight increase in the risk of asthma and wheezing with prenatal use of acetaminophen by mothers. Researchers speculate that acetaminophen's lack of inhibition of cyclooxygenase, the key enzyme involved in the inflammatory response of asthma, may be one explanation for the potential link between acetaminophen use and asthma. "

04 November 2009

22 October 2009

Bandolier Evidence-Based guides

Here are some examples

Other general pain control stuff

Palliative and supportive care

Pain care before, during, and after operations

Dysmenorrhoea (menstrual cramps)

18 September 2009

Why papercuts hurt so damn much

the rate of tissue damage is a direct function of protein in activation that, in turn, is a function of temperature. However, the amount of tissue damage is a function of both skin temperature and duration of stimulation. Since heat-induced pain depends only on the temperature attained by the cells of the skin and on duration of stimulation, pain intensity follows the rate of tissue damage and not its total amount. One consequence of this phenomenon is that some extensive wounds may be less painful than slight wounds. Pain from tissues that have suddenly become inflamed, such as a toothache, is an example." [Page 11; italics original]

A role for glial cell-targeting treatments for pain?

Under normal circumstances glial cells are thought to be like housekeepers, said Watkins. They essentially clean up debris and provide support for neurons.

But, like Gremlins, they have a nasty side too

[the researchers] believe they have figured out how morphine affects glial cells and neurons. 'We've found that different receptors are involved in how morphine suppresses pain through its actions on neurons versus how morphine activates glial cells,' Watkins said. 'What this means is that you should be able to separate the suppressive effects of morphine -- its pain-reducing effects through its action on neurons -- from all of its bad effects when it excites glial cells.'

(Via Psychology of Pain.)

19 August 2009

More sting connoisseurship

On reflection, it is quite funny how much power a drop of venom gives a little tiny bug over us:

Oh, Sting, Where Is Thy Death? - Happy Days Blog - NYTimes.com: The pain index came into being, he said, because he wanted to understand the two ways stinging can be of defensive value to an insect. ‘One is that it can actually do serious damage, to kill the target or make it impaired. The other is the whammy, the pain.’ He could quantify the amount of venom injected and its toxicity, but he had no way to measure pain other than through direct experience. So the pain index gave him a tool for interpreting an insect’s overall defensive strategy.

In fact, most insect stings do no damage at all, except to the two percent of people who suffer an allergic reaction. They just scare the wits out of us. And this is why they fascinate Schmidt: We typically outweigh any insect tormentor by a million times or more. We can outthink it. ‘And yet it wins,’ said Schmidt, ‘and the evidence that it has won is that people flap their arms, run around screaming, and do all kinds of carrying on.’ It wins ‘by making us hurt far more than any animal that size ought to be able to do. It deceives us into thinking serious damage is being done.’ And that’s generally enough to deliver the insect’s message, which is: Stay away from me and my nest."

At least, its funny when a harvester ant whose sting “felt like somebody was putting a knife in and twisting it” makes the point. Less so, when it comes from sterner teachers

A wasp known in the American Southwest as the “tarantula hawk” made him lie down and scream: “The good news is that by three minutes, it’s gone. If you really use your imagination you can get it to last five.” On the other hand, the sting of a bullet ant in Brazil (4-plus on the pain index) had him “still quivering and screaming from these peristaltic waves of pain” twelve hours later, despite the effects of ice compresses and beer.

Redheads need more drugs

The Pain of Being a Redhead - Well Blog - NYTimes.com:

A growing body of research shows that people with red hair need larger doses of anesthesia and often are resistant to local pain blockers like Novocaine. As a result, redheads tend to be particularly nervous about dental procedures and are twice as likely to avoid going to the dentist as people with other hair colors, according to new research published in The Journal of the American Dental Association.

Researchers believe redheads are more sensitive to pain because of a mutation in a gene that affects hair color. In people with brown, black and blond hair, the gene, for the melanocortin-1 receptor, produces melanin. But a mutation in the MC1R gene results in the production of a substance called pheomelanin that results in red hair and fair skin.

The MC1R gene belongs to a family of receptors that include pain receptors in the brain, and as a result, a mutation in the gene appears to influence the body’s sensitivity to pain. A 2004 study showed that redheads require, on average, about 20 percent more general anesthesia than people with dark hair or blond coloring. And in 2005, researchers found that redheads are more resistant to the effects of local anesthesia, such as the numbing drugs used by dentists.

[....]

It's also nice to hear that the research came from taking this sort of common experience seriously, rather than simply dismissing it:

Dr. Daniel I. Sessler, an anesthesiologist and chairman of the department of outcomes research at the Cleveland Clinic, said he began studying hair color after hearing so many colleagues speculate about redheads requiring more anesthesia.

‘The reason we studied redheads in the beginning, it was essentially an urban legend in the anesthesia community saying redheads were difficult to anesthetize,’ Dr. Sessler said. ‘This was so intriguing we went ahead and studied it. Redheads really do require more anesthesia, and by a clinically important amount.’

If I had red hair, I would bring a copy of the paper with me to the dentist/doctor to help them take my needs seriously.*

*Just as I would, for example, show literature on the usefulness of pre-incision lidocaine in lowering post-surgicial pain to my surgeon.

I might also post articles on the problems with using morphine in patients with kidney problems on the wall by an elderly relative's hospital bed.

Methadone prescribers' network

A New Service For Health Care Providers Who Prescribe Methadone To Treat Chronic Pain Or Opioid Addiction: "

A new service for health care providers prescribing methadone to treat chronic pain or opioid addiction -- the Physician Clinical Support System for Methadone (PCCS-M) -- opens this week with a mechanism to connect prescribers of methadone with experienced clinicians for one-to-one mentoring regarding the use of this medication.

Methadone is an inexpensive opioid medication that has several unique properties that make it particularly well suited to the treatment of chronic pain or opioid addiction, but it also has side effects and the potential for overdose and requires specific information for its proper use.

The new service is one in a number of federally-funded projects that address the need within the nation's health care system to provide safe and effective care of patients with chronic pain and opioid addiction while, at the same time, protecting the public from prescription drug abuse and diversion of medications. Using this new service, prescribers can contact a mentor, a knowledgeable colleague, by phone or e-mail with specific questions about the use of methadone for treating chronic pain or opioid addiction.

Source: American Society of Addiction Medicine "

As a general rule, I think drug policy should (strongly) promote the responsible clinician's ability to prescribe opioids as she sees fit . So, insofar as this sort of program can help stem diversion and accidental overdose, I'd much rather see more of these than more restrictive drug policies.

15 August 2009

Coral for neuropathic pain

New Hope Of Relief For Neuropathic Pain: "New Hope Of Relief For Neuropathic Pain

A compound initially isolated from a soft coral (Capnella imbricata) collected at Green Island off Taiwan, could lead scientists to develop a new set of treatments for neuropathic pain - chronic pain that sometimes follows damage to the nervous system.

[....]

Recent research suggests inflammation in the nervous system is a major causative factor for this condition. Inflammation activates supporting cells, such as microglia and astrocytes, that surround the nerve cells. These activated cells release compounds called cytokines that can excite nerves carrying pain sensation (nociceptive pathways) and cause the person to experience mildly uncomfortable stimuli as very painful (hyperalgesia), or stimuli that would normally induce no discomfort at all as painful (allodynia). Thus, cold drafts or lightly brushing the skin can produce intense pain, severely affecting the person's quality of life.

[....]

Although the chemical they studied, capnellene, was originally isolated in 1974, it is only recently that scientists have started to appreciate its potential. Capnellene is interesting because its structure is very different from pain-relieving drugs currently in use. Initial experiments suggested that it may have pain-relieving properties. Working with Yen-Hsuan Jean MD, PhD and other colleagues, Dr Wen tested capnellene and a second very similar compound, in isolated microglial cells and in experimental models of the condition in rats.

They found that the compounds significantly reduced pain-related activities in isolated microglia, and that these compounds also significantly reversed hyperalgesic behaviour in the experimental rats.

"

14 July 2009

Mindfulness in cancer treatment

Aided by a Proponent of Mindfulness, Cancer Patient Focuses on Joys of Today - washingtonpost.com

Why are you still here?

It's awesome. Trust me.

Okay fine. Don't believe me. Here's a small bit of its awesomeness to entice you:

Sanderson realized that this was what she was doing with her needle and, ultimately, with her illness: letting her experience of the present moment be overtaken by her fears for the future. Every hour she spent ruminating about the pain that was awaiting her was another hour she wasn't fully engaged with her life, another hour she couldn't enjoy. She couldn't pretend she didn't know her prognosis. So she chose a different route.

"I realized," she told us, "that the moments of pain -- even if the pain was excruciating -- were actually very short compared with the pain I put myself through by thinking about it ahead of time." If she could stay focused on the present moment no matter what she was doing -- washing dishes, talking to a colleague, even chatting with the doctor just before her treatment -- up until the moment the needle actually pierced her skin, she could cope. Even more, if she could keep that same focus from meandering to thoughts about what lay ahead in the future in general, she could continue to make the most of every moment that was not painful.

Some people think being positive means being certain of a cure. For others, it means enjoying the kindness of a friend or the mischief of a child or a rerun of "Battlestar Galactica" today, and leaving tomorrow's sorrows for tomorrow. For me, it meant.....

Oh you want to know how it ends don't you?

Now do you believe me?

Go read it. I'll still be here when you get back.

H/T: LB

Confusing 'ameliorating' with 'obliterating'

"We physicians are called upon to "ameliorate" pain, which often is considered synonymous with "obliterating" pain."

This is a very important flip-side to the incredible advances that have been made in pain medicine and public expectations about treatment.

The way 'ameliorate' and 'obliterate' have gotten run together in the public's (and even in many physicians') expectations has a significant downside: In addition to being annoying and disappointing to all involved, there's a case to be made that this sometimes (often?) leads to worse treatment outcomes.

For example, if a patient expects complete relief from her pain, partial relief might leave her depressed, frustrated, and resigned. Attitudes like those can be some of the biggest factors in determining how bad a pain is.* This is especially the case with many chronic pain conditions.

Of course, we've come a long way from seeing pain as an inevitable concomitant of disease and treatment, and thus not a direct concern for the physician.

And, we've to a large degree gotten over the invidious tendency to heap moral condemnation upon those who don't suffer in silence, and to see all pains, including medical pains, as deserved (the words 'pain' and 'punishment' both have their roots in 'poena').

On that note, this story in the Boston Globe is important: The Day Pain Died: What Really Happened During the Most Famous Moment in Boston Medicine

So, I suppose its worth keeping some perspective on how much attitudes and expectations have come in a very short amount of time. Still, there's still a long way left to go.

--

*As always: These attitudes are not merely responses to the pain, they can become part of the pain itself.

It is a serious conceptual mistake to think of a patient who feels helpless and resigned in the face of her pain as (necessarily) being in two bad states:

(a) Her pain is bad to degree xand

(b) Feeling helpless and resigned is bad to degree y.

Rather, these feelings are themselves parts of the pain. Their treatment is just as much a treatment of the pain itself as is the administration of morphine.

03 July 2009

Elderly headaches

Abstract Although the prevalence of headache in the elderly is relevant, until now few studies have been conducted in patients over the age of 65 years. We analyzed the clinical charts of 4,417 consecutive patients referred to our Headache Centre from 1995 to 2002. There were 282 patients over 65 years of age at the first visit, corresponding to 6.4% of the study population. Primary headaches were diagnosed in 81.6% of the cases, while secondary headaches and non-classifiable headaches represented, respectively, 14.9% and 3.5% of the cases. Among primary headaches, the prevalence was almost the same for migraine without aura (27.8%), transformed migraine (26.1%) and chronic tension- type headache (25.7%). The most frequent secondary headaches were trigeminal neuralgia and headache associated with cervical spine disorder."

By: C. Lisotto1, F. Mainardi, F. Maggioni, F. Dainese and G. Zanchin

DOI:10.1007/s10194-004-0066-9

01 July 2009

Percocet and Vicodin be gone (hopefully)

Panel Recommends Ban on 2 Popular Painkillers - NYTimes.com

By GARDINER HARRIS

Published: June 30, 2009

ADELPHI, Md. — A federal advisory panel voted narrowly on Tuesday to recommend a ban on Percocet and Vicodin, two of the most popular prescription painkillers in the world, because of their effects on the liver.

[....]

The agency is not required to [....] follow the recommendations of its advisory panels, but it usually does.

Unfortunately

But they voted 20 to 17 against limiting the number of pills allowed in each bottle, with members saying such a limit would probably have little effect and could hurt rural and poor patients. Bottles of 1,000 pills are often sold at discount chains.

‘We have no data to show that people who overdose shop at Costco,’ said Dr. Edward Covington, a panel member from the Cleveland Clinic Foundation.

IIRC, the problem is that their parents do. The patients who intentionally take handfuls of acetaminophen are usually teenage girls in initial and not-fully-serious suicide attempts. Few other countries allow the sort of bulk packaging we do.

Finally, I find this very hard to bellieve:

Still, some doctors predicted that the recommendation would put extra burdens on physicians and patients.

‘More people will be suffering from pain,’ said Dr. Sean Mackey, chief of pain management at Stanford University Medical School. ‘More people will be seeing their doctors more frequently and running up health care costs.’

The recommendation doesn't attempt to ban acetominophen. And, the 1,000 pill bottles are relatively cheap, so its hard to see too much of an increase in marginal cost if a patient will also have to buy the acetominophen OTC.

Moreover, why would more people go to the doctor because they have to get their oxycodone and acetominophen separately? Why would they go more frequently?

Indeed,

“It ties the doctor’s hands when you put the two drugs together,” said Dr. Scott M. Fishman, a professor of anesthesiology at the University of California, Davis, and a former president of the American Academy of Pain Medicine. “There’s no reason you can’t get the same effect by using them separately.” Dr. Fisher said the combinations were prescribed so often for the sake of convenience, but added, “When you’re using controlled substances, you want to err on the side of safety rather than convenience.”

Fingers crossed that the FDA will follow the recommendation....

25 June 2009

Whose problem is the diversion of opioids?

Anyway, I was annoyed by not knowing I feel this way.* So, the following is some off-the-cuff noodling about when concerns are relevant in decisions about the use of opioid drugs. I'm not at all sure about how much of it I want to stand behind. But hopefully it might be useful for sparking some discussion.

*I remember someone once telling me that philosophy starts with a sense of wonder. I have since found that, for me, it usually starts with annoyance; it ends in wonder.

-------------

In general, I tend to think that the dangers of opioid diversion --opioids ending up outside of the patient's hands-- get too much weight in discussions of drug policy (although some recent statistics on overdose and death rates involving opioids are giving me some pause in my beliefs about the severity of diversion's harms).

But in addition to questions about how severe the consequences of diversion are, we also need to know whose problem it is. A comprehensive drug policy spans many different areas including, inter alia, the law in its criminal, civil, and regulatory forms; professional determinations of best clinical practices; and individual clinicians' decisions about how to treat individual patients. Thus we need to know whether preventing diversion should have the same importance for everyone involved in the prescription drug arena.

I'm going to suggest that preventing diversion can be a legitimate concern at the more general levels. And they may inform doctors practices in a general way. But, I suspect, the potential harms resulting from diversion should not factor into a doctor's decisions about what medications to prescribe a patient.

My claims here will rest on the supposition that a clinician's ethical responsibilities arise from her patient's individual welfare. Her professional obligation is not the promotion of the general welfare via her interactions with a certain individual. The clinician's responsibility is to alleviate her patient's suffering in the safest and most effective way available.

A rough analogy may help bring out this distinction between duties based in the promotion of the general welfare and duties based in the promotion of an individual's welfare. In an adversarial system of criminal justice like we have in the United States, the role of a defense attorney is to advocate for her clients interests as best she can. Even if she recognized that her client's conviction may benefit the public at large, she is obligated to ignore that fact in doing her job. This doesn't mean that the job of defense attorney is entirely removed from the enterprise of promoting the public good. It's that a system in which a party is assigned to look out only for the interests of the defendant is more likely to be better overall. (One major disanalogy here is that my supposition about the source of the doctor's duties need not appeal to claims about what would best promote the general welfare.)

If we a clinician's duties as tied her patient's welfare in this way, concerns about the welfare of others are thus (nearly always) irrelevant to decisions about what substances to prescribe her patient. This suggests that even though the clinician may foresee that others may be harmed through diversion if she prescribes an opioid to a patient, this possibility should have no weight in her decision about what to prescribe. Her duty arises from and is directed at the health of her patients, not the health of people in general.

Obviously, this has its limits. Massive harms to others may trump this obligation. And it may be that if two treatments were exactly equal in their efficacy and safety, then considerations of the general good or other effects on others may break the tie.

Nor does this mean that the doctor must completely ignore the possibility that the drug will be diverted. Other public entities' interests in preventing diversion are based in their obligation to protect public health overall. But given the source of her professional obligations, the clinician's concerns about diversion should be limited to its effects on her patient's health.

Clearly, a responsible clinician must be attuned to the possibility that the patient herself will divert the drug. But her vigilance is not demanded by the need to prevent harms to the recipients of the diversion. It comes from her responsibilities to the patient. The clinician's treatment decisions must be based on the supposition that the patient will comply with the prescribed regime. She cannot aim to promote an individual's welfare by prescribing her a substance that she believes that the patient will not take. Therefore, the belief that the patient will take the drug as prescribed is a necessary condition of justifiably prescribing an opioid.

Suppose that a patient is accompanied by a stoned adolescent whose T-shirt reads "I love drugs!" Does this necessary condition imply that she ought to take into consideration the likelihood that the son will divert the drugs?

The answer seems to be yes. She cannot prescribe a medication to benefit her patient if she believes that the patient won't take the drug because someone else will steal it. Of course, it's unlikely that the suspicion in this case would justify her refusing to prescribe an otherwise indicated opioid Much will hang on the strength of her conviction that the drug will be diverted. In the drug diverting adolescent case, the clinician may be required to put special emphasis on the need to keep control of the medication in counseling the patient. But as long as she can be satisfied that the patient will be reasonably vigilant, she will be justified in writing the prescription. Her uncertainty about the likelihood of diversion combined with the need to respect the patient's autonomy will set the bar for reasonable vigilance pretty low.

Cases in which she should altogether refuse to prescribe on these grounds will likely be rare. But they are easy to imagine. Suppose that a disabled patient is completely dependent on her caretaker for all of her medications. If the clinician was convinced that the caretaker would divert a significant portion of the prescribed opioid, then she should not write the prescription. Indeed, doing so would be tantamount to writing the prescription for the caretaker. Though, she may have some obligation to seek other ways of getting the indicated treatment to the patient (e.g., recommending at home nursing visits, and patient treatment).

What's important is the way concerns about diversion are figuring in here. A clinician should be cautious of diversion insofar as it would interfere with her patient's treatment. Her responsibilities do not depend on how the recipients of the diverted substance may be affected. Those dangers of diversion give her reason to, for example, keep her cabinets locked. But they should be irrelevant to her decisions about patients' treatments.

This is not to say that a comprehensive drug policy should not be concerned about the harms to non-patients who gain access to opioids through diversion. It is a fact that the availability of opioids in legitimate channels will involve some diversion and some non- patients will be harmed. While the clinician's responsibility is based in her individual patient's welfare, government policies are properly attuned to protecting welfare across the board. Thus entities (in the US) like the FDA, the Department of Justice and the DEA are justified in creating policies and enforcement practices which will minimize the amount of diversion.

But this picture of the clinician's obligations does create tension between the government's proper aims creating drug policy and the duties of clinicians. We should thus want a principled way of resolving these kinds of inevitable conflict. One possibility is that one set of considerations will always trump the other (that is, the first set is lexically prior to the other).

To see the implications of a lexical ordering of these considerations suppose that the paramount consideration in shaping drug policy was ensuring clinicians' abilities to carry out their duties to their patients. This would have implications for how we decide conflicts. Such a partial lexical ordering would entail that the protection of access to safe and effective drugs cannot be trumped by considerations about diversion. More generally, this might mean that any proposed policy that would promote the general good could be vetoed if it unreasonably affected the ability of clinicians to treat their patients.

This ordering of concerns would be unlikely to undermine reasonable restrictions on the use and prescription of opioids. For example, this is compatible with a well regulated and organized system for inventory control in the manufacturing, shipping, and distribution of opioids. The same is true for methods of verifying the legitimacy of prescriptions and the identity of patients. But some apparently relatively mild restrictions on prescribing ability may not be compatible with this set of drug policy priorities.

For example, the FDA is presently considering requiring all clinicians who prescribe powerful long-acting opioids to have a special certification. Many general practice clinicians who currently prescribe such medications may be unwilling to go through the hassle of obtaining and maintaining the certification. If the certification process was unduly difficult, many clinicians would be unable to prescribe the medications that they thought were best indicated for their patients conditions. Such a regulation would likely decrease the number of deaths from diversion. But no matter how many diversion related deaths would be prevented, it should be rejected if we believe that the clinician's abilities to treat their patients should always trump any other consideration.

So, in sum, here's what I've suggested: If we think about the source and nature of clinicians' professional obligations in a particular way, then concerns about diversion should not play a role in determining whether to prescribe an opioid (outside of diversion undermining the treatment regime). Direct focus on preventing diversion is instead the job of regulatory agencies whose mission is the common public good.

I haven't given any argument in favor of the further idea that concerns about diversion should always be subordinated to clinicians ability to prescribe opioids as they see fit. Though I am definitely attracted to this view. We can leave that a subject for another post.

Opioids often preferable to NSAID's in the elderly

The NYT reports that in light of findings that

[in elderly patients] The risks of Nsaids include ulcers and gastrointestinal bleeding and, with some drugs, an increased risk of heart attacks or strokes. The drugs do not interact well with medicines for heart failure and other conditions, and may increase high blood pressure and affect kidney function, experts said.

The American Geriatrics Society

removed those everyday medicines, called Nsaids, for nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, from the list of drugs recommended for frail elderly adults with persistent pain. The panel said the painkillers should be used “rarely” in that population, “with extreme caution” and only in “highly selected individuals.”

[....]

“We’ve come out a little strong at this point in time about the risks of Nsaids in older people,” said Dr. Bruce Ferrell, a professor of geriatrics at U.C.L.A. who is chairman of the panel. “We hate to throw the baby out with the bathwater — they do work for some people — but it is fairly high risk when these drugs are given in moderate to high doses, especially when given over time.

“It looks like patients would be safer on opioids than on high doses of Nsaids for long periods of time,” he continued

Link (My italics; I've interpolated the order of the paragraphs)

Editorial comment: I'm unhappy that the reporter chose to use this quote in emphasizing that opioids have their own dangers:

“We’re seeing huge increases nationwide of reports about the misuse and diversion of prescription drugs and related deaths,” said Dr. Roger Chou, a pain expert who was not involved in writing the guidelines for the elderly but directed the clinical guidelines program for the American Pain Society. “The concerns about opioids are very real.”

Diversion of opioids is a real problem. But it really annoys me to see it used as a counterpoint in discussions of their clinical usefulness.

I almost feel like these claims are saying something like: Advil might kill Grandma, but we might not want to give her a safer treatment because her grandson might steal it and kill himself.' (I don't think the reporter or Dr. Chou intended it this way --that's just how I take it)

Update: I was bothered by not knowing why the stuff about diversion annoys me so much. So I've posted some very rough thoughts here.

16 June 2009

Resources for Causalgia (CRPS/RSD)

Resources and Relief for Reflex Sympathetic Dystrophy

For those of you who don't know, Causalgia (CRPS/RSD) should rank high on the list of 'Things-You-Don't-Want'.

On the IASP definition:

Causalgia

A syndrome of sustained burning pain, allodynia, and hyperpathia after a traumatic nerve lesion, often combined with vasomotor and sudomotor dysfunction and later trophic changes.

Or as it was first described by Silas Weir Mitchell in 1872 after the Civil War

"We have some doubt as to whether this form of pain ever originates at the moment of the wounding. . . Of the special cause which provokes it, we know nothing, except that it has sometimes followed the transfer of pathological changes from a wounded nerve to unwounded nerves, and has then been felt in their distribution, so that we do not need a direct wound to bring it about. The seat of the burning pain is very various; but it never attacks the trunk, rarely the arm or thigh, and not often the forearm or leg. Its favorite site is the foot or hand. . . Its intensity varies from the most trivial burning to a state of torture, which can hardly be credited, but reacts on the whole economy, until the general health is seriously affected....The part itself is not alone subject to an intense burning sensation, but becomes exquisitely hyperanesthetic, so that a touch or tap of the finger increases the pain." quoted in UCLA pain exhibit

In other words, in causalgia part of your body feels like it's constantly on fire.

Online introduction to pain processes

Philosophers will, of course, carefully take note the role of C nociceptive afferents.

11 June 2009

ABC story on FDA Acetaminophen overdose report

Like the changing of the leaves, experts call for better public education and packaging practices.

And, like the migration of the butterflies^, the pharmaceutical industry tells them to go f*** themselves:

McNeil Consumer Healthcare, a Johnson & Johnson subsidiary and the manufacturer of Tylenol, said in a statement Thursday that they fear the [FDA report's] recommendations could have the effect of steering consumers away from an appropriate and safe drug.