November 25, 2003

The Delicate Balance Of Pain and Addiction

By BARRY MEIER

Over the past two decades, conflicting medical ideas have surfaced about narcotic painkillers, the drugs that Rush Limbaugh blames for his addiction while being treated for chronic back pain. And both of them, not surprisingly, have centered on the bottom-line question: just how great a risk of abuse and addiction do narcotics pose to pain patients?

Throughout much of the last century, doctors believed that large numbers of patients who used these drugs would become addicted to them. That incorrect view meant that cancer sufferers and other patients with serious pain were denied drugs that could have brought them relief.

But over the past decade, a very different viewpoint has emerged, one championed by doctors specializing in pain treatment and drug companies eager to broaden the market for such drugs. It held that these medications posed scant risk to pain patients, and some experts now believe that it also had unfortunate consequences because it caused, among other things, physicians to develop a false sense of security about these drugs.

''The pendulum went in two opposite directions,'' said Dr. Bradley S. Galer, group vice president for scientific affairs at Endo Pharmaceuticals, which manufactures two widely used narcotics, Percodan and Percocet. ''Luckily, now the pendulum is focusing where it should be, right in the middle.''

The reassessment of narcotic risk comes at a time of skyrocketing rates of misuse and abuse of such drugs. Medical experts agree that most pain patients can successfully use narcotics without consequences. But the same experts also say that much remains unknown about the number or types of chronic pain sufferers who will become addicted as a result of medical care, or ''iatrogenically'' addicted. The biggest risk appears to be to patients who have abused drugs or to those who have an underlying, undiagnosed vulnerability to abuse substances, a condition that may affect an estimated 3 to 14 percent of the population.

Dr. James Zacny, an associate professor at the University of Chicago and a leading narcotics researcher, said there was a dearth of data about the long-term risks that narcotics pose. ''We don't know a lot about the rate of iatrogenic addiction,'' he said.

It is not unusual for views about particular drugs and their hazards to change over time. But a look at the shift in medical thinking about the risk of addiction shows a struggle that was waged both as a guerrilla war among doctors and a high-powered drug industry initiative. It was also an effort that, while seeking a laudable goal, inaccurately portrayed science.

Modern views about the threat posed to patients by narcotics were shaped in the mid-1980's when pain treatment experts reported that cancer patients treated with such drugs did not exhibit the type of euphoria displayed by people who abused narcotics. That led some physicians to argue that strong, long-acting narcotics could also be used safely to treat patients with serious pain unrelated to cancer, like persistent back pain or nerve disorders.

One leader of this initiative, known as the ''pain management movement,'' was Dr. Russell Portenoy, who is now chairman of the pain medicine and palliative care department at Beth Israel Medical Center in New York. And soon Dr. Portenoy and others were pointing to studies that they said backed up their contention that the risk of powerful narcotics to pain patients was scant.

''There is a growing literature showing that these drugs can be used for a long time, with few side effects and that addiction and abuse are not a problem,'' Dr. Portenoy said in a 1993 interview with The New York Times.

Drug companies amplified that theme in materials sent to doctors and pharmacists. For example, Janssen Pharmaceutica, the producer of Duragesic, called the risk of addiction ''relatively rare'' in a package insert with the drug. Endo termed the risk ''very rare'' in presentations to hospital pharmacists. Purdue Pharma, the manufacturer of the powerful narcotic OxyContin, distributed a brochure to chronic pain patients called ''From One Pain Patient to Another,'' contending that it and similar drugs posed minimal risks.

''Some patients may be afraid of taking opioids because they are perceived as too strong or addictive,'' the brochure stated. ''But that is far from actual fact. Less than 1 percent of patients taking opioids actually become addicted.''

The trouble, however, was that studies that looked at the experience of pain patients who used long-acting narcotics for extended periods of time did not exist. So narcotics advocates like Dr. Portenoy and drug companies like Purdue Pharma had looked elsewhere, at surveys of patients whose use of narcotics was limited. And those reports were not always put into proper context.

A frequently cited survey of narcotics use, taken in 1980, found ''only four cases of addiction among 11,882 hospitalized patients.'' A director of that survey, Dr. Hershel Jick, an associate professor of medicine at Boston University, said his study did not follow patients after they left the hospital and did not address the risk of narcotics when they were prescribed in outpatient settings.

In another case, advocates of increased narcotics use also misstated a study's results. It involved a study of chronic headache sufferers conducted at the Diamond Headache Clinic in Chicago that some pain care specialists repeatedly claimed had found only ''three problem cases'' among some 2,000 patients.

While the Diamond Headache Clinic did treat 2,369 patients in the study period, just 62 were studied because they met the criteria of having used painkillers alone or in combination with barbiturates for six months before entering the clinic. And the report's findings were far different from the way they were characterized by narcotics advocates. It concluded, ''There is a danger of dependency and abuse in patients with chronic headaches.''

Dr. Seymour Diamond, the clinic's director, said in a recent interview that neither pain experts nor narcotics manufacturers like Purdue Pharma who cited his study contacted him to discuss how they planned to use it. And he added that he believed that it was mischaracterized.

''It distorts the picture and it clearly underplays the risks,'' Dr. Diamond said.

In a recent interview, Dr. Portenoy said he now had misgivings about how he and other pain specialist used the research. He said that he had not intended to mischaracterize it or to mislead fellow doctors, but that he had tried to counter claims that overplayed the risk of addiction. Still, he and others acknowledge, the campaign by pain specialists and drug companies has had consequences.

''In our zeal to improve access to opioids and relieve patient suffering, pain specialists have understated the problem, drawing faulty conclusions from very limited data,'' Dr. Steven D. Passik, a pain management expert wrote in a 2001 letter published in The Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. ''In effect, we have told primary care doctors and other prescribers that the risk was so low they essentially could ignore the possibility of addiction.''

Today, some narcotics manufacturers like Endo have changed or are changing the way they present abuse and addiction information. For example, Purdue Pharma, while maintaining the accuracy of its past position, now states in patient information that it does ''not know how often patients with continuing (chronic) pain become addicted to narcotics but the risk has been reported to be small.'' Ligand Pharmaceuticals, which manufactures a time-released form of morphine under the brand name Avinza, makes a similar statement.

For its part, a spokeswoman for the federal Food and Drug Administration, Kathleen K. Quinn, said the agency believed that ''the risk of addiction to chronic pain patients treated with narcotic analgesics has not been well studied and is not well characterized.''

In a letter to The New York Times, Purdue stated that it had found no cases of iatrogenic addiction in a recently completed long-term study of chronic pain patients suffering from osteoarthritis, diabetes and low pain back. Purdue did not identify where it planned to submit the study for publication although the company said it involved an older group of patients whose average age was 55.

Such results are encouraging. But several pain experts said that the full risks of narcotics will not be fully known until these drugs are tested in a wide range of pain patients of different ages and conditions.

''You may have a study telling how uncommon these problems are in patients over 50,'' Dr. Portenoy said. ''But what does that tell you about the risks to younger patients or those patients who walk into a doctor's office with a history of substance abuse or psychological problems.''

Link

03 May 2017

Blast from the past: Addiction fears and palliative care

17 February 2017

Stoics on pain

Pain is an opinion that some present thing is a bad of such a sort that we should be downcast about it.

[Cambridge Companion to the Stoics, p.270]

07 February 2017

Why so little attention to physical evil?

In these centuries...prior to the development of medicine and its pain-killing or controlling drugs, and when very severe penalties, imposed by Church and State alike, were commonly acceptable, the problems of physical evil do not appear to have been taken as seriously as they are by contemporary thinkers. [Connellan, Why Does Evil Exist? p.9]

04 January 2017

19 November 2016

Abnormal sensory states

Allodynia: lowered threshold: stimulus and response mode differ

Hyperalgesia: increased response: stimulus and response mode are the same

Hyperpathia: raised threshold: stimulus and response mode may be the increased response: same or different

Hypoalgesia: raised threshold: stimulus and response mode are the same lowered response:

The above essentials of the definitions do not have to be symmetrical and are not symmetrical at present. Lowered threshold may occur with allodynia but is not required. Also, there is no category for lowered threshold and lowered response - if it ever occurs.

Link

05 October 2016

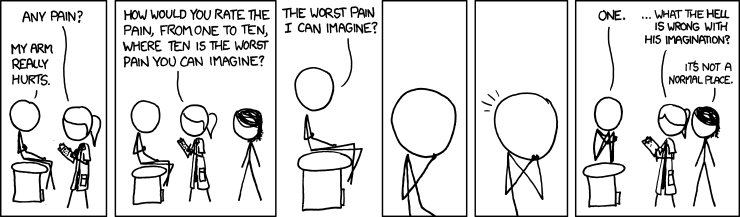

More on pain rating scales, xkcd weighs in

Following up on Hyperbole and a Half's critique of the Wong-Baker Scale, xkcd weighs in on anchors of common assessment scales.

His mouseover caption presses the point: "If it were a two or above, I couldn't answer because it would mean a pause in the screaming."

This reminds me of a conversation with a friend about the pragmatics of rating the pain which brought you to the doctor's office. Our consensus: Rating the pain a 6 is high enough that the doctor will take you seriously, but not so high that they think you're lying or make the wrong diagnosis.

10 August 2016

Catrastrophizing in pain paper

Blackwell Synergy - Pain Medicine, OnlineEarly Articles (Article Abstract)

Jo Nijs PhD, Karen Van de Putte MSc, Fred Louckx PhD, Steven Truijen PhD, Kenny De Meirleir PhD (2007)

Exercise Performance and Chronic Pain in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: The Role of Pain Catastrophizing

doi:10.1111/j.1526-4637.2007.00368.x

Exercise Performance and Chronic Pain in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: The Role of Pain Catastrophizing

ABSTRACT

Objectives. This study aimed to examine the associations between bodily pain, pain catastrophizing, depression, activity limitations/participation restrictions, employment status, and exercise performance in female patients with chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) who experience widespread pain.

Design. Cross-sectional observational study.

Setting. A university-based clinic.

Patients. Thirty-six female CFS patients who experienced widespread pain.

Outcome Measures. Patients filled in the Medical Outcomes Short-Form 36 Health Status Survey, the Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Activities and Participation Questionnaire, the Beck Depression Inventory, and the Pain Catastrophizing Scale, and underwent a maximal exercise stress test with continuous monitoring of electrocardiographic and ventilatory parameters.

Results. Pain catastrophizing was related to bodily pain (r = −0.70), depression (r = 0.55), activity limitations/participation restrictions (r = 0.68), various aspects of quality of life (r varied between −0.51 and −0.64), and exercise capacity (r varied between −0.41 and −0.61). Based on hierarchical multiple regression analysis, pain catastrophizing accounted for 41% of the variance in bodily pain in female CFS patients who experience chronic widespread musculoskeletal pain. Among the three subscale scores of the Pain Catastrophizing Scale, helplessness and rumination rather than magnification were strongly related to bodily pain. Neither pain catastrophizing nor depression was related to employment status.

Conclusions. These data provide evidence favoring a significant association between pain catastrophizing, bodily pain, exercise performance, and self-reported disability in female patients with CFS who experience widespread pain. Further prospective longitudinal studying of these variables is required.

28 May 2016

The Almost Discovery Of Anesthesia : NPR

Here's an NPR story on the discovery of nitrous oxide. The transcript and podcast are here:

No, Thank You; We Like Pain: The Almost Discovery Of Anesthesia : NPR

Today's Quantified Self practitioners take note, you've got nothing on young Humphry Davy.

07 March 2016

Placebo ethics related papers

ScienceDirect - Pain : Don’t ask, Don’t tell? Revealing placebo responses to research participants and patients

An NIMH perspective on the use of placebosBiological Psychiatry

Biological Psychiatry, Volume 47, Issue 8, 15 April 2000, Pages 689-691Steven E. Hyman and David Shore

The placebo in modern medicine

Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, Volume 43, Issue 2, Part 1, 1996, Pages 76-79

Stephen E. Silvis

Classical conditioning and the placebo effect

Pain, Volume 72, Issues 1-2, August 1997, Pages 107-113

Guy H. Montgomery and Irving Kirsch

Abstract

Stimulus substitution models posit that placebo responses are due to pairings of conditional and unconditional stimuli. Expectancy theory maintains that conditioning trials produce placebo response expectancies, rather than placebo responses, and that the expectancies elicit the responses. We tested these opposing models by providing some participants with information intended to impede the formation of placebo expectancies during conditioning trials and by assessing placebo expectancies. Although conditioning trials significantly enhanced placebo responding, this effect was eliminated by adding expectancies to the regression equation, indicating that the effect of pairing trials on placebo response was mediated completely by expectancy. Verbal information reversed the effect of conditioning trials on both placebo expectancies and placebo responses, and the magnitude of the placebo effect increased significantly over 10 extinction trials. These data disconfirm a stimulus substitution explanation and provide strong support for an expectancy interpretation of the conditioned placebo enhancement produced by these methods.

Placebo and Nocebo in Cardiovascular Health: Implications for Healthcare, Research, and the Doctor-Patient RelationshipJournal of the American College of Cardiology, Volume 49, Issue 4, 30 January 2007, Pages 415-421

Brian Olshansky

Abstract

Despite treatments proven effective by sound study designs and robust end points, placebos remain integral to elicit effective medical care. The authenticity of the placebo response has been questioned, but placebos likely affect pain, functionality, symptoms, and quality of life. In cardiology, placebos influence disability, syncope, heart failure, atrial fibrillation, angina, and survival. Placebos vary in strength and efficacy. Compliance to placebo affects outcomes. Nocebo responses can explain some adverse clinical outcomes. A doctor may be an unwitting contributor to placebo and nocebo responses. Placebo and nocebo mechanisms, not well understood, are likely multifaceted. Placebo and nocebo use is common in practice. A successful doctor-patient relationship can foster a strong placebo response while mitigating any nocebo response. The beneficial effects of placebo, generally undervalued, hard to identify, often unrecognized, but frequently used, help define our profession. The role of the doctor in healing, above the therapy delivered, is immeasurable but powerful. An effective placebo response will lead to happy and healthy patients. Imagine instead the future of healthcare relegated to a series of guidelines, tests, algorithms, procedures, and drugs without the human touch. Healthcare, rendered by a faceless, uncaring army of protocol aficionados, will miss an opportunity to deliver an effective placebo response. Wise placebo use can benefit patients and strengthen the medical profession.

The placebo in modern medicine, ,Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, Volume 43, Issue 1, January 1996, Pages 76-79

Stephen E. Silvis

Abstract

View More Related Articles

FindText

Bookmark and share in 2collab (opens in new window)

Request permission to reuse this article

View Record in Scopus

Cited By in Scopus (0)

doi:10.1016/j.pain.2008.01.009

Editorial

Don’t ask, Don’t tell? Revealing placebo responses to research participants and patients

Francis KeefeCorresponding Author Contact Information, a, E-mail The Corresponding Author, Amy P. Abernethyb, Jane Wheelerb and Glenn Affleckc

aPain Prevention and Treatment Research Program, Duke University Medical Center, Suite 340, 2200 Main Street, Durham, NC 27705, USA

bDuke Cancer Care Research Program, Division of Medical Oncology, Department of Medicine, 25165 Morris Building, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC 27710, USA cUniversity of Connecticut Health Center, USA

Available online 20 February 2008.

Refers to: Revelation of a personal placebo response: Its effects on mood, attitudes and future placebo responding

Pain, Volume 132, Issue 3, 5 December 2007, Pages 281-288

S. Karen Chung, Donald D. Price, G. Nicholas Verne and Michael E. Robinson

14 December 2015

Blast from the past

Ouch!

Monday, Jan. 01, 1945

People like Dickens' Mrs. Gummidge, who claim they "feel more than other people do," will have a chance to prove it in the future. For Cleveland's Dr. Lorand Julius Bela Gluzek has rigged up an efficient little machine called a dolorimeter, which measures pain in grams. It would have made the Marquis de Sade very happy. Just put the victim's leg on the leg rest, put the pressure inductor on his shin bone and pump up the pressure until it hurts. That indicates the threshold at which pain begins (and the victim—however Spartan—is supposed to yell). The threshold varies from 500 (for the Gummidge type) to 2,700 grams, depending on the person's nervous system.

The dolorimeter is also used on people who already have a pain. It can measure pain anywhere in the body—Marat's itch, Prometheus' pecked liver and Job's ulcers would have been equally fair game. The machine is applied to the patient's leg and the squeeze increased beyond the threshold, up & up until the agonized shin bone makes the patient forget his neuralgia or whatever was hurting him. A reading at that point gauges the severity of the neuralgia, the sores or the itch. By comparing the first day's pain intensity with successive days' recordings, the progress of the complaint can be charted. According to last week's Modern Medicine, Dr. Gluzek (who apparently thinks that all pigs caught under a gate squeal equally loud) has made 16,000 readings, finds his dolorimeter accurate in 97% of the pains measured.

20 September 2015

NYT on chronic pain

Pain, the Disease

By MELANIE THERNSTROM

A modern chronicler of hell might look to the lives of chronic-pain patients for inspiration. Theirs is a special suffering, a separate chamber, the dimensions of which materialize at the New England Medical Center pain clinic in downtown Boston. Inside the cement tower, all sights and sounds of the neighborhood -- the swans in the Public Garden, the lanterns of Chinatown -- disappear, collapsing into a small examining room in which there are only three things: the doctor, the patient and pain. Of these, as the endless daily parade of desperation and diagnoses makes evident, it is pain whose presence predominates.

''Yes, yes,'' sighs Dr. Daniel Carr, who is the clinic's medical director. ''Some of my patients are on the border of human life. Chronic pain is like water damage to a house -- if it goes on long enough, the house collapses. By the time most patients make their way to a pain clinic, it's very late.'' What the majority of doctors see in a chronic-pain patient is an overwhelming, off-putting ruin: a ruined body and a ruined life. It is Carr's job to rescue the crushed person within, to locate the original source of pain -- the leak, the structural instability -- and begin to rebuild: psychically, psychologically, socially.

For leaders in the field like Carr, this year marks a critical watershed. In January, the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations, the basic national health care review board, implemented the first national standards requiring pain assessment and control in all hospitals and nursing homes. Standards for evaluating and managing pain in lab animals have long been tightly regulated, but curiously there had never before been any legal equivalent for people. Maine took the further step last year of passing its own legislation requiring the aggressive treatment of pain, and California and other states are considering following suit.

''It's a field on the verge of an explosion,'' Carr says. ''There's no area of medicine with more growth and more public interest. We've come far enough scientifically to see how far we have to go.''

Chronic pain -- continuous pain lasting longer than six months -- afflicts an estimated 30 million to 50 million Americans, with social costs in disability and lost productivity adding up to more than $100 billion annually. However, only in recent years has it become a focus of research. There used to be no pain specialists because pain had always been understood as a symptom of underlying disease: treat the disease and the pain should take care of itself. Thus, specializing in pain made no more sense than specializing in fever. Yet the actual experience of patients frequently belied this assumption, for chronic pain often outlives its original causes, worsens over time and appears to take on a puzzling life of its own.

Research has begun to shed light on this: unlike ordinary or acute pain, which is a function of a healthy nervous system, chronic pain resembles a disease, a pathology of the nervous system that produces abnormal changes in the brain and spinal cord. New technology, like functional imaging, which is generating the first portraits of brains in action, is revealing the nature of pain's pathology.

Far from being simply an unpleasant experience that people should endure with a stiff upper lip, pain turns out to be harmful to the body. Pain unleashes a cascade of negative hormones like cortisol that adversely affect the immune system and kidney function. Patients treated with morphine heal more quickly after surgery. A recent study suggests that adequate cancer-pain treatment may influence the prospects for survival: rats with tumors given morphine actually live longer than those that do not receive it.

Paradigm shifts occur slowly; if arriving at a new medical conception of pain has been difficult and protracted, disseminating the knowledge will be more so. Pain treatment belongs primarily in the hands of ordinary physicians, most of whom know little about it. Less than 1 percent of them have been trained as pain specialists, and medical schools and textbooks give the subject very little attention. The primary painkillers -- opiates, like OxyContin -- are widely feared, misunderstood and underused. (A 1998 study of elderly women in nursing homes with metastatic breast cancer found that only a quarter received adequate pain treatment; one-quarter received no treatment at all.)

While the undertreatment of pain has led to lawsuits -- recently, a California court issued a judgment against a Bay Area internist for undertreating a terminally ill patient's cancer pain -- so has the overprescribing of OxyContin in cases of patient abuse. It takes only a few lawsuits -- along with the threat of Drug Enforcement Administration oversight and regulation -- to exert a chilling effect on prescribing practices. ''Doctors feel damned if they do and damned if they don't,'' says Dr. Scott Fishman, chief of the division of pain medicine at the University of California at Davis Medical Center. ''The enormous confusion about pain has led to the hysteria around opiates.''

Dr. James Mickle, a family doctor in rural Pennsylvania, describes the leeriness most physicians feel about treating pain: ''Is it objective or subjective? How do you know you're not being tricked or taken advantage of to get narcotics? And chronic-pain patients are, generally, well -- a pain. Most doctors' reaction to a patient with chronic pain is to try to pass them off to someone who's sympathetic.''

And what makes a doctor sympathetic to pain?

''Someone who has pain himself,'' Mickle says. ''Or has an intellectual interest -- who isn't interested in immediate results, doesn't want to make money, has a lot of degrees. There's one in a lot of communities, but then they get all the pain patients sent to them and eventually they burn out and quit.''

Daniel Carr's interest in pain began as an intellectual one. After training as an internist and endocrinologist, he published a landmark study in 1981 of runners, which showed that exercise stimulates beta-endorphin production, leading to a ''runner's high'' that temporarily anesthetizes the runner. He began to wonder: if the runner's high is an example of how a healthy body successfully modulates pain, what abnormality leads to chronic pain? He did a third residency in anesthesia and pain medicine, became a founder of the multidisciplinary pain clinic at Massachusetts General Hospital and a director of the American Pain Society. Six years ago, he moved to Tufts and set up a pain clinic (which loses money) and created the country's first master's program in pain for health professionals.

Every pain patient is a testament to the dangers of the conservative wait-it-out approach to pain, as a day spent in Carr's clinic demonstrates. But it is the last patient of the day, Lee Burke, whose story proves the most instructive, because her diagnosis turns out to be so simple, while the forces that worked against it being made earlier were so complex.

Seven years ago, Burke -- a delicately featured 56-year-old woman in a blue cotton sweater that picks up the blue of her eyes and the gray in her hair -- learned she had one of the most survivable varieties of brain tumors, a growth known as an acoustic neuroma behind her left ear. The recovery period from the surgery to remove it was supposed to be a mere seven weeks. Instead, she awoke from surgery with an unforeseen problem. She had headaches -- lancinating lightning, hot pain -- that knocked her out for periods ranging from four hours to four days. She never returned to her job as an executive at a real-estate company. When pain came between her and her husband, she left him -- and her money and her home. ''It was easier to be alone with the pain,'' Burke says.

Carr asks her to describe the headaches. Like most of the 100-odd patients I observed in various pain clinics trying to describe their suffering, Burke seems stumped by the question. Therein lies a specific damnation of pain. As Elaine Scarry writes in her seminal book, ''The Body in Pain,'' pain is not a linguistic experience; it returns us to ''the world of cries and whispers.'' Patients grope at far-fetched metaphors. ''A hot, banging pain, like an ice pick,'' says one. ''It heats up and then sticks it in, again and again.''

Says Burke: ''It's like being slammed into a wall and totally destroyed. It makes you want to pull every hair out of your head. There's nothing I can do to defend myself.'' She looks at Carr with the particular stricken bewilderment -- why and why me? -- that I saw on the faces of so many pain patients. Pain, from the Latin word for punishment, poena, can feel like the work of a torturer who must have -- but won't reveal -- a purpose. ''It's like knives are going through my eyes,'' she says, starting to weep.

While she blots her face, Carr sits calmly, his concentration fixed, his hands folded reassuringly across his lap, with the equable, impersonal kindness of a priest or a cop. Almost all of the patients during the long day have broken down in their appointments. Perhaps because their lives echo the chaos in his own blue-collar Irish-Catholic upbringing as the son of an alcoholic bartender, he says, he isn't alarmed when patients scream at him. He is neither indifferent to emotion nor distracted by it; you sense at all times that his focus is on the culprit -- the shape-shifter, the pain.

Carr asks Burke to close her eyes and taps her head with the corner of an unopened alcohol wipe. Within a few minutes he has found a clear pattern of numbness that suggests that one of the main nerves in her face -- the occipital nerve -- was severed or damaged during her surgery. It is clear from their differing expressions that Carr regards this as revelation -- the demystification of her pain -- and that Burke has no idea why.

Pain makes a child of everyone. Her voice becomes small as she asks, ''If the nerve was cut, why does it cause pain?''

It is a question researchers have only recently been able to answer. Doctors used to be so confident that severed nerves could not transmit pain -- they're severed! -- that nerve cutting was commonly prescribed as a treatment for pain. But while cut motor nerves can be counted on to cause paralysis, sensory nerves are tricky. Sometimes they stay dead, causing only numbness. But sometimes they grow back irregularly or begin firing spontaneously and produce stabbing, electrical or shooting sensations.

Picture the pain wiring of the nervous system as an alarm, the body's evolutionary warning system that protects it from tissue injury or disease. Acute pain is like a properly working alarm system: the pain proportionally matches the amount of damage, and it disappears when the underlying problem does. Chronic pain is like a broken alarm: a wire is cut and the entire system goes haywire. ''This is true pathology -- the repair doesn't occur, because the system itself is damaged,'' explains Clifford Woolf, an M.D.-Ph.D. pain researcher and the director of Mass. General's neuroplasticity lab. It is called neuropathic pain because it is a pathology of the nervous system.

Woolf was the first to answer an old puzzle: why does chronic pain often worsen over time? Why doesn't the body develop tolerance? Woolf's research demonstrated that physical pain changes the body in the same way that emotional loss watermarks the soul. The body's pain system is plastic and therefore can be molded by pain to cause, yes, more pain. An oft-used metaphor is that of an alarm continually reset to be more sensitive: first it is triggered by a cat, then a breeze and then for no reason it begins to ring randomly or continuously. As recent research by Allan Basbaum at the University of California at San Francisco has shown, with prolonged injury progressively deeper levels of pain cells in the spinal cord are activated. Pain nerves recruit others in a ''chronic-pain windup,'' and the whole central nervous system revs up and undergoes what Woolf calls ''central sensitization.''

Lee Burke's records do not even note whether her occipital nerve was cut, and her surgeon may not have noticed the dental-floss-size nerve. It took more than a year of complaints before she was referred to Dr. Martin Acquadro, the director of cancer pain at Mass. General, who noted that she had severe muscle spasms in her head, neck and shoulders. It was a classic pain misinterpretation: he seized on muscular pain as the primary problem, rather than a secondary symptom, and diagnosed tension headaches.

He treated her with Botox injections, tricyclic antidepressants and migraine medications. She tried range-of-motion physical therapy, stress-reduction courses, psychiatric treatment, yoga and meditation and consumed 3,200 milligrams of ibuprofen a day, along with 12 cups of coffee (caffeine is a treatment for migraines). He steered her away from opiates with warnings about their addictive qualities.

Until recently, opiates were the only serious pain drug available. But neuropathic pain is the kind of pain for which opiates are the least effective. In the past few years, however, an alternative has come along. A new antiseizure drug, Neurontin, has been found to also act as a nerve stabilizer that can quiet the misfiring nerves responsible for neuropathic pain.

When I call her four months after the appointment with Carr, Burke says she feels 50 percent better from a combination of Neurontin and other drugs. The muscle spasms -- so rigid that Acquadro compared them to railroad tracks -- had melted. She no longer needed a snorkel for her daily swim because she could move her head from side to side again. Of course, you have to be in terrible pain to find the side effects of pain drugs tolerable. But while her headaches sometimes required so much Neurontin that she was too dazed to walk, she was glad to be able to sit up to watch television instead of simply lying prone in agony.

''Dr. Carr is my savior,'' she says. I recall the way she left the appointment, clasping his hand as if she wanted to kiss it and looking at him with hope so intense it was hard to watch.

''There's tremendous ignorance about neuropathic pain,'' Woolf says. ''Most doctors don't know to look for it.'' One confusing factor is that not all patients with similar conditions develop chronic pain. Neuropathic pain seems to require genetic vulnerability. Pain clinics are filled with patients with ordinary conditions and extraordinary pain. M.R.I.'s show only bones and tissue; doctors might look at a patient's scan and say, ''Your back looks fine -- the muscle swelling is gone'' or ''The bone's all healed,'' and conclude there is no reason for pain. But the pain is not in the muscles or bones; it is in the invisible hydra of the nerves.

Of course, not all chronic pain is neuropathic -- there is inflammatory pain, for example, or muscular pain. But many chronic-pain conditions, like backache, which was once assumed to be wholly musculoskeletal, are now thought to have a neuropathic component.

About 10 percent of women used to complain of chronic pain following radical mastectomies. Their pain had always been interpreted as a psychological phenomenon: they were just ''missing'' their breasts. But in the early 1980's, Dr. Kathleen Foley at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York identified the pain as being caused by the severing of a major thoracic nerve during surgery, and the technique was revised.

Doctors warn patients of many risks, from death to scarring, but rarely mention the not-uncommon side effect of chronic pain. The life of one of Carr's patients was ruined by having a nerve nicked during plastic surgery to correct protruding ears. Another acquired chronic chest pain after being treated in a hospital for a collapsed lung when a tube was inserted in her chest -- one of the most nerve-rich areas in the body. One especially poignant category of patients in pain clinics is that of those who have had surgery specifically to treat chronic -- usually back -- pain where the surgery leads to new, worse pain, an outcome for which they say they had no warning.

Pain doctors have many theories about why these kinds of things happen, but the dialogue is frustratingly one-sided. There are no spokesmen for undertreating pain -- no one advocates not treating pain.

Although I contacted many of the former doctors of pain patients, it was rare that one was willing to examine his decisions thoughtfully, as Martin Acquadro did. It was immediately clear to me that Acquadro, a licensed dentist as well as an anesthesiologist, was both competent and caring and that the forces that delayed Burke's treatment were not personal shortcomings but genuine, pervasive confusions about pain.

Acquadro thought the pain of all acoustic neuroma patients should manifest itself similarly, and most of those he had seen did, in fact, ''respond to simpler, more holistic therapies.'' He had not thought of Neurontin, and he feared opiates. ''We don't always do patients a favor putting them on high-dose narcotics,'' he says. ''When a patient is depressed or anxious, you're leery about narcotics or alcohol. With Lee, I guess I'd have to say I was being cautious.'' His voice changes -- softens and quiets -- as he gets to the real point: ''I was afraid.''

Like many doctors, he says he felt comfortable with anti-inflammatory drugs, although the 3,200 milligrams of ibuprofen that Burke took daily put her at risk for gastrointestinal bleeding. According to the Federal Drug Abuse Warning Network, anti-inflammatory drugs (including aspirin and Aleve) were implicated in the deaths of 16,000 people in 2000 because of bleeding ulcers and related complications. While large doses of the drugs are sometimes needed to treat inflammation, opiates are a much safer -- and generally more effective -- analgesic.

Although far fewer than 1 percent of pain patients using opiates develop any addictive behavior, opiates have a reputation for being dangerous, and social biases -- class, race and sex -- influence who is entrusted with them. Studies by Dr. Richard Payne at Sloan-Kettering show that minorities are up to three times as likely as others to receive inadequate pain relief -- and to have their requests for medication interpreted as bad ''drug-seeking behavior.'' A study conducted by Dr. William Breitbart at Sloan-Kettering found that women with H.I.V. are twice as likely to be undertreated for pain as men. Many of Carr's patients have some social strike against them that led their previous doctors to withhold treatment: two were workers' compensation cases, one was mentally ill, several had histories of substance abuse, all of them were poor and most were women.

Women tend to be either less aggressive in demanding pain treatment or to be aggressive in ways that are misinterpreted as hysteria. The longer pain goes untreated, the more desperate and crazed the patient becomes -- until those behaviors look like the problem. Burke recalls that whenever Acquadro sent her to other specialists -- headache specialists, balance specialists and behavioral pain-medicine specialists -- she would break down during the appointments in pain and frustration. ''They all just figured I was a basket case,'' she says. ''And I was. I was a basket case.''

Rather than dismiss her psychic distress, Acquadro seems to have become overly focused on it, trying to explain her pain through that prism: ''Lee's pain seemed to be better at the times she was happier, was forming new relationships or helping others,'' he says. ''And even though she was motivated and worked hard on stress reduction, the fact remains, she is a tense person.''

Naturally. Everyone who has chronic pain eventually develops anxiety and depression. Anxiety and depression are not merely cognitive responses to pain; they are physiologic consequences of it. Pain and depression share neural circuitry. The hormones that modulate a healthy brain, like serotonin and endorphins, are the same ones that modulate depression. Functional-imaging scans reveal similar disturbances in brain chemistry in both chronic pain and depression.

''Chronic pain uses up serotonin like a car running out of gas,'' says Breitbart. ''If the pain persists long enough, everybody runs out of gas.'' Thus, Acquadro's not treating Burke's pain aggressively because she was ''tense'' is like ''not rescuing someone who is drowning because they're having a panic attack,'' according to Breitbart. Difficulty breathing triggers panic as reliably as pain causes depression. When serotonin is inhibited in laboratory animals, morphine ceases to have an analgesic effect on them. Medications that treat depression also treat pain. Depression or stressful events can in turn enhance pain. Since Sept. 11, pain clinics have been fuller. ''If we started putting sugar in the water, it would affect the diabetics first -- pain patients respond to stress with increased pain,'' explains Scott Fishman, who also trained as a psychiatrist. But to make stress reduction a primary strategy for pain treatment is trying to repaint the walls of a crumbling house.

It is an easy mistake to make -- and one I made myself. i developed pain five years ago for, what seemed to me, absolutely no reason. A fiery sensation flared in my neck, flowed through my right shoulder and sizzled in my hand. It didn't feel like normal pain -- it felt like a demon had rested a hand on my shoulder. Suddenly I tasted brimstone and burning.

Two years later, an M.R.I. would reveal spinal stenosis, a narrowing of the spinal canal, and cervical spondylosis, a type of arthritis, both of which squeeze the nerves and cause pain to radiate into my shoulder and hand. But in the meantime, I was convinced that if I steadfastly ignored it, the pain would eventually go its own way. I tried to treat it as a psychological problem. Many pain patients have had doctors who pathologized them, told them their pain was unreal; I pathologized myself, hoping my pain was unreal -- or that it would become so if I treated it as such.

I analyzed the pain in psychotherapy. I tried acupuncture, massage and herbal remedies. I read books about conversion hysteria, the placebo effect and Sufis who thread fishhooks through their pectoral muscles. What I didn't read was anything that might have actually informed me about my symptoms, like Fishman's excellent patient-oriented book, ''The War on Pain.'' Nor did I consult any clarifying Web sites, like painfoundation.org.

When the pain depressed me, I focused on the depression. I adopted Dr. John E. Sarno's popular creed that muscular tension syndrome is the source of most back ills and faithfully scrutinized my life for stress. It is one of those circular self-confirming hypotheses: when I was happy and my pain light, I took it as confirmation of the correlation; when I was happy but had a lot of pain, I wondered if I didn't want to be happy. I recall how, strapped inside the white crypt of the M.R.I. machine for more than an hour, I tried to calm myself by repeating the motto of my Christian Scientist grandparents: ''There is no life, truth, intelligence nor substance in matter. All is infinite Mind and its infinite manifestation.'' But I sensed the machine was seeing my pain in its own way and that its report would be irrefutable. My pain would no longer be a tree falling in the forest with no one to hear it. The greatest fear pain patients have, doctors sometimes say, is that it is ''all in their heads.'' But infinitely scarier, I thought as I lay there, is the fear that it isn't.

His is the new frontier of medicine,'' Clifford Woolf says heatedly in his clipped South African accent. ''What we're learning is that chronic pain is not just a sensory or affective or cognitive state. It's a biologic disease afflicting millions of people. We're not on the verge of curing cancer or heart disease, but we are closing in on pain. Very soon, I believe, there will be effective treatment for pain because, for the first time in history, the tools are coming together to understand and treat it.''

The most important tool in his lab at Mass. General -- a vast landscape of test tubes filled with rat DNA -- is the new ''gene chip'' technology that identifies which genes become active when neurons respond to pain. ''In the past 30 years of pain research, we've looked for pain-related genes, one at a time, and come up with 60. In the past year, using gene-chip technology, we've come up with 1,500,'' Woolf says happily. ''We're drowning in new information. All we have to do is read it all -- to prioritize, to find the key gene, the master switch that drives others.''

Woolf is particularly interested in certain abnormal sodium ion channels that are only expressed in sensory neurons that have been damaged. He believes he is close -- perhaps a year away -- from identifying which among these channels is the most important one. Then -- if his animal data applies to humans -- pharmaceutical companies could design blockers for these channels, and after the years it takes to develop a new drug, there could be a cure for neuropathic pain.

On the table before us in Woolf's lab, a graduate student is piercing the sciatic nerve of a white rat. The rat is of a pain-sensitive variety, one prone to developing neuropathic pain. In 10 days, when Woolf cuts open the rat's brain, he will be able to discern the imprint of the sciatic nerve injury. There will be corresponding maladaptive changes in the way the brain processes and generates pain.

The biggest question of pain research is whether this pathological cortical reorganization can be undone. A 1997 University of Toronto study has shown disturbing implications. Anna Taddio compared the pain responses of groups of infant boys who had been circumcised with and without anesthesia. Four to six months later, the latter group had a lowered pain threshold, crying more at their first inoculations -- providing evidence that there is cellular pain memory of damage to the immature nervous system.

Terms like ''pathological cortical reorganization'' and ''cellular pain memory'' have a very ominous ring. Are these children really doomed to be more sensitive to pain their entire lives? Will a cure for neuropathic pain help all the people who already have it -- or only prevent others from developing it?

Woolf looks at me and hesitates. ''We don't really know,'' he says tactfully. Another pause. ''In the present state, no.'' However, he says, even if the damage cannot be undone, treatment could still help suppress the abnormal sensitivity. ''But obviously, it's going to be much easier to prevent the establishment of abnormal channels than to treat the ones already there.'' He sighs, rests his head against his hand. ''Obviously.''

I want to ask another question, but I'm overcome by a rare unreporterly desire. I want him to get back to work.

Melanie Thernstrom is the author of ''The Dead Girl'' and ''Halfway Heaven: Diary of a Harvard Murder.''

* Copyright 2007 The New York Times Company

* Home

* Privacy Policy

* Search

* Corrections

* XML

* Help

* Contact Us

* Work for Us

* Back to Top

Link

06 June 2015

Pain proverbs

Pain mingles with pleasure.

Source: (Latin)

Pain of mind is worse than pain of body.

Source: (Latin)

Pain past is pleasure.

Source: (Latin)

http://www.worldofquotes.com/proverb/Latin/26/index.html

04 February 2015

Hospice and opioids paper

Blackwell Synergy - Pain Medicine, Volume 7 Issue 4 Page 320-329, July/August 2006 (Article Abstract)

Toward Evidence-Based Prescribing at End of Life: A Comparative Analysis of Sustained-Release Morphine, Oxycodone, and Transdermal Fentanyl, with Pain, Constipation, and Caregiver Interaction Outcomes in Hospice Patients

Poster presented during the 20th annual meeting of the American Academy of Pain Medicine, March 3–7, 2004, Orlando, FL.

ABSTRACT

Objective. The primary goal of this investigation was to examine selected outcomes in hospice patients who are prescribed one of three sustained-release opioid preparations. The outcomes examined include: pain score, constipation severity, and ability of the patient to communicate with caregivers.

Patients and Settings. This study included 12,000 terminally ill patients consecutively admitted to hospices and receiving pharmaceutical care services between the period of July 1 and December 31, 2002.

Design. We retrospectively examined prescribing patterns of sustained-release morphine, oxycodone, and transdermal fentanyl. We compared individual opioids on the aforementioned outcome markers, as well as patient gender, terminal diagnosis, and median length of stay.

Results. Patients prescribed a sustained-release opioid had similar average ratings of pain and constipation severity, regardless of the agent chosen. Patients prescribed transdermal fentanyl were reported to have more difficulty communicating with friends and family when compared with patients prescribed either morphine or oxycodone. On average, patients prescribed transdermal fentanyl had a shorter length of stay on hospice as compared with those receiving morphine or oxycodone.

Conclusion. There was no difference in observed pain or constipation severity among patients prescribed sustained-release opioid preparations. Patients receiving fentanyl were likely to have been prescribed the medication due to advanced illness and associated dysphagia. Diminished ability to communicate with caregivers and a shorter hospice course would be consistent with this profile. Further investigation is warranted to examine the correlation between a patient’s ability to interact with caregivers and pain control achieved.

06 January 2015

Religion and sickle cell pain

Author(s):M.O. Harrison, C.L. Edwards and H.G. Koenig.

Source:Pain Digest 16.2 (March-April 2006): p106(1). (175 words)

Document Type:Magazine/Journal

Bookmark:Bookmark this Document

Library Links:

*

Full Text :COPYRIGHT 2006 Springer

Examination of the impact of three domains of religiosity/spirituality (church attendance, prayer/Bible study, intrinsic religiosity) on measures of pain in individuals with sickle cell disease (SCD). Research has demonstrated positive associations between religiosity/spirituality and better physical and mental health outcomes. However, few studies have examined the influence of religiosity/spirituality on the experience of pain in chronically ill patients. A consecutive sample of 50 SCD outpatients was studied. Church attendance was significantly associated with measures of pain. Attending church once or more per week was associated with the lowest scores on pain measures. These findings were maintained after controlling for age, gender, and disease severity. Prayer/Bible study and intrinsic religiosity were not significantly related to pain. Conclude that positive associations are consistent with recent literature, but the present results expose new aspects of the relationship for African American patients. Religious involvement likely plays a significant role in modulating the pain experience of African American patients with SCD.

(Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina, USA) J Nerv Merit Dis 2005:193(4):250-257.

17 December 2014

The Clinical Art of Pain Medicine: Balancing Evidence, Experience, Ethics, and Policy

Blackwell Synergy - Pain Medicine, Volume 6 Issue 4 Page 277-279, July 2005 (Full Text)

The Clinical Art of Pain Medicine: Balancing Evidence, Experience, Ethics, and Policy

* Rollin M. Gallagher, MD, MPH

Editor-in-Chief

Efficacy, effectiveness, morbidity risks, and costs are four metrics that inform our conscious clinical reasoning about treatment for each patient. These metrics also inform general treatment strategies for different patient groups defined by characteristics such as mechanism, disease, age, comorbidities, and insurance coverage. Physician factors such as bias and values, sometimes unconscious, may also affect clinical reasoning. The Spine Section herein, while arguing best practices for zygapophysial blocks, highlights the importance of carefully considering the source and meaning of our metrics in pain medicine practice.

Efficacy tells us about the chances of pain relief and its expected magnitude from any treatment, based on double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trials in specific clinical populations. Effectiveness, a less precise metric usually derived from extended open label clinical trials and clinical experience, informs us of the performance of a treatment in a practice setting where factors such as convenience, comorbidities, and tolerability influence our decisions. Tricyclic antidepressants for neuropathic pain or depression are a good example––efficacy is established, but effectiveness in the field, which is enhanced by side-effects such as nighttime sedation and by once-a-day dosing convenience, is limited by both side-effect burden and concerns about toxicity and drug–disease interactions (e.g., arrhythmias, hypotension, urinary retention, suicide). Morbidity risks may emerge in early clinical trials, but sometime only after large populations are exposed to a particular drug or procedure in routine clinical practice over years or in large, postapproval multicenter trials. Nonsteroid anti-inflammatory drug (NSAIDS) (gastrointestinal and renal risk), Cox 2 inhibitors (cardiovascular risk), and spinal surgery for nonspecific low back pain (failed back surgery syndrome) are examples of risks that emerged in the public's awareness long after treatments were widely used in the field. Costs may influence practitioners’ decisions about what to recommend, and patients’ decisions about what prescriptions to fill and what advice to follow. Managed care plans require time-consuming preapproval for many treatments and may sanction physician outliers. Well-insured or wealthy patients often ignore cost, which for others may preclude filling a prescription or using it correctly ("a little is better than none"). As a general rule, when medicine fails to develop cost-effectiveness models for practice, a business model prevails and restricts practice. Business knows that withholding treatment for costs implies an administrative, rather than therapeutic, relationship to the patient, and that this position is uncomfortable for most physicians.

What is our metric for deciding when a procedure is justified for any one patient? Can we weigh the cost-effectiveness of a treatment against our patient's hopes for relief ? If initial treatment is ineffective, when does our own insecurity influence our decisions? When is consultation appropriate? Dr. Schofferman [1] reminds us that conventional wisdom based on extensive research suggests that a two-point reduction in pain on a 0–10 scale is clinically significant and that many investigators consider a 50% improvement to be significant when evaluating efficacy [2]. In our practices we chip away at the pain, using the additive benefit of several modalities to bring the pain down to a level that enables the patient to enjoy a meaningful quality of life. Ultimately, a level 4 may be as low as we can get without intolerable side-effects; if level 4 improves quality of life and achieves a patient's desired goals (if not complete relief, then return to work or other meaningful activity), we consider treatment successful. Complete relief often seems ephemeral in pain clinics for two reasons: first, the "simple" cases with one or a few isolated lesions causing pain that respond to a block or neuroablative procedure may be treated successfully before referral; second, the cases that are referred have more complex pain (multiple mechanisms, including progressive tissue damaging disease or central nervous system damage) or more complex clinical problems (e.g., medical or psychiatric comorbidities). This reality indicates the fundamental problem with our model of sequential care in pain medicine––we often do not see the patient until after a succession of treatment failures by others, and the resulting complications of poor pain relief [3].

Articles by Drs Barnsely [4] and Bogduk [5] in the Spine Section argue another perspective––that only complete relief from pain, no pain, is the gold standard outcome upon which treatments should be judged. Barnsley, in a study of a consecutive sample of patients who underwent neurotomy of the medial branches of the cervical dorsal rami to palliate chronic zygapophysial joint pain, used complete relief of pain as the indicator of successful outcome. This was obtained for 36 of 45 cases (80%) for a mean of 35 weeks and is, indeed, a very impressive result. Although this study is not placebo controlled, the magnitude of effect (complete relief) argues strongly for effectiveness. (A recent study of subanesthetic ketamine in complex regional pain syndrome [6], using a similar metric, similarly argues for the effectiveness of a new treatment in what many have considered a treatment-resistant disease). Bogduk's review of the evidence for the efficacy of steroid injections into lumbar zygapophysial joints uses the same criterion for success. However, his review suggests little more than placebo effect for this procedure when used in the lumbar region.

Schofferman's commentary [1] cogently present a different perspective. He argues that pain specialists, particularly experienced clinicians, often treat outliers, patients that do not conform to the strict selection criteria required in a research protocol. These patients may have several causes of pain and are more likely to have failed conventional treatment and to have comorbidites. He suggests that the clinical art of medicine, informed by but not dictated by evidence-based medicine (EBM), should determine our behavior as clinicians. He also suggests that ethical principles ("do no harm") inform these decisions––that not doing something that might relieve pain, when its potential harm is minimal and the chances of success reasonable, given the available information, is not "best practices."

I agree that practicing the clinical art of pain medicine should be guided by this combination of values (evidence, clinical needs, and ethics) in pain practice (see Dubois M, Pain Medicine 2005;6[3]). We should add to that equation the value of a mindfulness of social policy. This perspective is particularly important for a field engaged now in a struggle to establish its professional authority through EBM and public accountability. The physician caring for a patient with unrelenting pain feels a moral imperative to ease suffering. Some may respond by trying anything that might work. If it is well reimbursed, then, as Dr. Bogduk suggests, our economic "imperative" is satisfied, and we are gratified in testing our clinical skills. Many consider this posture irresponsible, because it jeopardizes our professional standing as a field. A more nuanced approach, recognizing all the factors that might influence outcome, is needed. Trying a procedure as an isolated treatment without addressing a patient's risks for poor outcome is unwise clinically and, to many, unethical because of its cumulative negative effects on social policy as regards our specialty. The ultimate negative outcome would be reducing the public's access to our effective treatments. Although today this behavior may be reimbursed, it reduces our professional authority and makes tomorrow's reimbursement for our effective procedures less likely. The highest clinical art imbeds procedures in a plan that addresses other salient risks, thus improving cost-effectiveness and enhancing our reputation. Ultimately, calm demeanor and reasoned judgment, informed by education, training, experience, ethical principles, and emerging evidence, is the medical product that society will deem invaluable.

1 Schofferman J. Commentary to a narrative review of intra-articular corticosteroid injections for low back pain. Pain Med 2005; 6( 4): 297– 8 .

2 Farrar J, Young J, LaMoreaux L, Werth J, Poole M. Clinical importance of changes in chronic pain intensity measured on an 11-point numerical pain rating scale. Pain 2001; 94: 149– 58.

3 Gallagher RM. Pain medicine and primary care: A community solution to pain as a public health problem. Med Clin North Am 1999; 83( 5): 555– 85.

4 Barnsley L. Percutaneous radiofrequency neurotomy for chronic neck pain: Outcomes in a series of consecutive patients. Pain Med 2005; 6( 4): 282– 6 .

5 Bogduk N. A narrative review of intra-articular corticosteroid injections for low back pain. Pain Med 2005; 6( 4): 287– 96 .

6 Correll GE, Maleki J, Gracely EJ, Muir JJ, Harbut RE. Subanesthetic ketamine infusion therapy: A restrospective analysis of a novel therapeutic approach to complex regional pain syndrome. Pain Med 2004; 5( 3): 263– 75.

02 December 2014

More links: Racial and ethnic disparities in pain

Blackwell Synergy - Pain Medicine, Volume 6 Issue 1 Page 5-10, January 2005 (Article Abstract)

Pain Medicine

Volume 6 Issue 1 Page 5-10, January 2005

Louis W. Sullivan MD, Barry A. Eagel MD (2005) Leveling the Playing Field: Recognizing and Rectifying Disparities in Management of Pain

Pain Medicine 6 (1) , 5–10 doi:10.1111/j.1526-4637.2005.05016.x

Salimah H.Meghani, MSN, CRNP, Doctoral Candidate Nursing/MBE. (2005) Leveling the Playing Field: Does Pain Disparity Literature Suffer from a Reporting Bias?. Pain Medicine 6:3, 269–270The

Ethical Implications of Racial Disparities in Pain: Are Some of Us More Equal?

Allen Lebovits, PhD

Pain Medicine, Volume 6, Issue 1, Page 3-4, Jan 2005, doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2005.05013.x

21 November 2014

Some links: Racial and ethnic disparities in pain

Blackwell Synergy - Pain Medicine, Volume 4 Issue 3 Page 277-294, September 2003 (Article Abstract)

Pain Medicine

Volume 4 Issue 3 Page 277-294, September 2003

To cite this article: Carmen R. Green MD, Karen O. Anderson PhD, Tamara A. Baker PhD, Lisa C. Campbell PhD, Sheila Decker PhD, Roger B. Fillingim PhD, Donna A. Kaloukalani MD, MPH, Kathyrn E. Lasch PhD, Cynthia Myers PhD, Raymond C. Tait PhD, Knox H. Todd MD, MPH, April H. Vallerand PhD, RN (2003) The Unequal Burden of Pain: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Pain

Pain Medicine 4 (3) , 277–294 doi:10.1046/j.1526-4637.2003.03034.x

Prev Article Next Article

You have full access rights to this content

Abstract

The Unequal Burden of Pain: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Pain

* Carmen R. Green, MDaaUniversity of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, Michigan; ,

* Karen O. Anderson, PhDbbM.D. Anderson Cancer Center Pain Research Group, Houston, Texas; ,

* Tamara A. Baker, PhDccUniversity of Michigan, School of Public Health, Ann Arbor, Michigan; ,

* Lisa C. Campbell, PhDddDuke University Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina; ,

* Sheila Decker, PhDeeUniversity of Iowa School of Nursing, Iowa City, Iowa; ,

* Roger B. Fillingim, PhDffUniversity of Florida College of Dentistry, Gainesville, Florida; ,

* Donna A. Kaloukalani, MD, MPHggWashington University, St. Louis, Missouri; ,

* Kathyrn E. Lasch, PhDhhNew England Medical Center, Boston, Massachusetts; ,

* Cynthia Myers, PhDiiUniversity of California Los Angeles, Los Angeles, California; ,

* Raymond C. Tait, PhDjjSt. Louis University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri; ,

* Knox H. Todd, MD, MPHkkEmory University, Rollins School of Public Health, Atlanta, Georgia; and , and

* April H. Vallerand, PhD, RNllWayne State University College of Nursing, Detroit, Michigan

*

aUniversity of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, Michigan; bM.D. Anderson Cancer Center Pain Research Group, Houston, Texas; cUniversity of Michigan, School of Public Health, Ann Arbor, Michigan; dDuke University Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina; eUniversity of Iowa School of Nursing, Iowa City, Iowa; fUniversity of Florida College of Dentistry, Gainesville, Florida; gWashington University, St. Louis, Missouri; hNew England Medical Center, Boston, Massachusetts; iUniversity of California Los Angeles, Los Angeles, California; jSt. Louis University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri; kEmory University, Rollins School of Public Health, Atlanta, Georgia; and lWayne State University College of Nursing, Detroit, Michigan

Carmen R. Green, MD, University of Michigan Medical School, Department of Anesthesiology, 1500 East Medical Center Drive, 1H247 UH—Box 0048, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109. Tel: (734) 936-4240; Fax: (734) 936-9091; E-mail: carmeng@umich.edu.

ABSTRACT

context.

Pain has significant socioeconomic, health, and quality-of-life implications. Racial- and ethnic-based differences in the pain care experience have been described. Racial and ethnic minorities tend to be undertreated for pain when compared with non-Hispanic Whites.

objectives.

To provide health care providers, researchers, health care policy analysts, government officials, patients, and the general public with pertinent evidence regarding differences in pain perception, assessment, and treatment for racial and ethnic minorities. Evidence is provided for racial- and ethnic-based differences in pain care across different types of pain (i.e., experimental pain, acute postoperative pain, cancer pain, chronic non-malignant pain) and settings (i.e., emergency department). Pertinent literature on patient, health care provider, and health care system factors that contribute to racial and ethnic disparities in pain treatment are provided.

evidence.

A selective literature review was performed by experts in pain. The experts developed abstracts with relevant citations on racial and ethnic disparities within their specific areas of expertise. Scientific evidence was given precedence over anecdotal experience. The abstracts were compiled for this manuscript. The draft manuscript was made available to the experts for comment and review prior to submission for publication.

conclusions.

Consistent with the Institute of Medicine's report on health care disparities, racial and ethnic disparities in pain perception, assessment, and treatment were found in all settings (i.e., postoperative, emergency room) and across all types of pain (i.e., acute, cancer, chronic nonmalignant, and experimental). The literature suggests that the sources of pain disparities among racial and ethnic minorities are complex, involving patient (e.g., patient/health care provider communication, attitudes), health care provider (e.g., decision making), and health care system (e.g., access to pain medication) factors. There is a need for improved training for health care providers and educational interventions for patients. A comprehensive pain research agenda is necessary to address pain disparities among racial and ethnic minorities.

This article is cited by:

* M. Carrington Reid, MD, PhD, Maria Papaleontiou, MD, Anthony Ong, PhD, Risa Breckman, MSW, Elaine Wethington, PhD, and Karl Pillemer, PhD. Self-Management Strategies to Reduce Pain and Improve Function among Older Adults in Community Settings: A Review of the Evidence. Pain Medicine doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2008.00428.x

Abstract Abstract and References Full Text Article Full Article PDF

* Margarette Bryan, MD, Nila De La Rosa, MSN, RN, APNC, OCN, Ann Marie Hill, MBA, William J. Amadio, PhD, and Robert Wieder, MD, PhD. Influence of Prescription Benefits on Reported Pain in Cancer Patients. Pain Medicine doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2008.00427.x

Abstract Abstract and References Full Text Article Full Article PDF

* Salimah H. Meghani, PhD, MBE, CRNP, and Rollin M. Gallagher, MD, MPH. Disparity vs Inequity: Toward Reconceptualization of Pain Treatment Disparities. Pain Medicine doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2007.00344.x

Abstract Abstract and References Full Text Article Full Article PDF

* Mary Jo Larson, Michael Paasche-Orlow, Debbie M. Cheng, Christine Lloyd-Travaglini, Richard Saitz & Jeffrey H. Samet. (2007) Persistent pain is associated with substance use after detoxification: a prospective cohort analysis. Addiction 102:5, 752–760

Abstract Abstract and References Full Text Article Full Article PDF

* Lisa Maria E. Frantsve, PhD, and Robert D. Kerns, PhD. (2007) Patient–Provider Interactions in the Management of Chronic Pain: Current Findings within the Context of Shared Medical Decision Making. Pain Medicine 8:1, 25–35

Abstract Abstract and References Full Text Article Full Article PDF

* Donna Kalauokalani, MD, MPH, Peter Franks, MD, Jennifer Wright Oliver, MD, Frederick J. Meyers, MD, and Richard L. Kravitz, MD, MSPH. (2007) Can Patient Coaching Reduce Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Cancer Pain Control? Secondary Analysis of a Randomized Controlled Trial. Pain Medicine 8:1, 17–24

Abstract Abstract and References Full Text Article Full Article PDF

* Raymond C. Tait, PhD. (2007) The Social Context of Pain Management. Pain Medicine 8:1, 1–2

Summary Abstract and References Full Text Article Full Article PDF

* Jacqueline S. Martin, R. Bingisser, R. Spirig. (2007) Schmerztherapie: Patientenpräferenzen in der Notaufnahme. Intensivmedizin und Notfallmedizin 44:6, 372

CrossRef

* Michael J. Platow, Nicholas J. Voudouris, Melissa coulson, Nicola Gilford, Rachel Jamieson, Liz Najdovski, Nicole Papaleo, Chelsea Pollard, Leanne Terry. (2007) In-group reassurance in a pain setting produces lower levels of physiological arousal: direct support for a self-categorization analysis of social influence. European Journal of Social Psychology 37:4, 649

CrossRef

* Annette L. Stanton, Tracey A. Revenson, Howard Tennen. (2007) Health Psychology: Psychological Adjustment to Chronic Disease. Annual Review of Psychology 58:1, 565

CrossRef

* Carmen R. Green. (2007) Racial and Ethnic Disparities in the Quality of Pain Care. Anesthesiology 106:1, 6

CrossRef

* A. Berquin. (2007) La médecine fondée sur les preuves : un outil de contrôle des soins de santé ? Application au traitement de la douleur. Douleur et Analgésie 20:2, 64

CrossRef

* Frank Brennan, Daniel B. Carr, Michael Cousins. (2007) Pain Management: A Fundamental Human Right. Anesthesia & Analgesia 105:1, 205

CrossRef

* Laurent G. Glance, Richard . Wissler, Christopher Glantz, Turner M. Osler, Dana B. Mukamel, Andrew W. Dick. (2007) Racial Differences in the Use of Epidural Analgesia for Labor. Anesthesiology 106:1, 19

CrossRef

* Cathy L. Campbell. (2007) Respect for Persons. Journal of Hospice & Palliative Nursing 9:2, 74

CrossRef

* Carmen Green, MD, Knox H. Todd, MD, Allen Lebovits, PhD, and Michael Francis, MD. (2006) Disparities in Pain: Ethical Issues. Pain Medicine 7:6, 530–533

Summary Abstract and References Full Text Article Full Article PDF

* Carole C. Upshur, EdD, Roger S. Luckmann, MD, MPH, Judith A. Savageau, MPH. (2006) Primary Care Provider Concerns about Management of Chronic Pain in Community Clinic Populations. Journal of General Internal Medicine 21:6, 652–655

Abstract Abstract and References Full Text Article Full Article PDF

* Robert A. Nicholson, PhD; Megan Rooney, MEd; Kelly Vo, MD; Erinn O'Laughlin, MPH; Melanie Gordon, MD. (2006) Migraine Care Among Different Ethnicities: Do Disparities Exist?. Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain 46:5, 754–765

Abstract Abstract and References Full Text Article Full Article PDF

* Diana J. Burgess, PhD, Michelle van Ryn, PhD, MPH, Megan Crowley-Matoka, PhD, and Jennifer Malat, PhD. (2006) Understanding the Provider Contribution to Race/Ethnicity Disparities in Pain Treatment: Insights from Dual Process Models of Stereotyping. Pain Medicine 7:2, 119–134

Abstract Abstract and References Full Text Article Full Article PDF

* John T. Chibnall, Raymond C. Tait, Elena M. Andresen, Nortin M. Hadler. (2006) Clinical and Social Predictors of Application for Social Security Disability Insurance by Workers??? Compensation Claimants With Low Back Pain. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 48:7, 733

CrossRef

* James Elander, Malgorzata Marczewska, Roger Amos, Aldine Thomas, Sekayi Tangayi. (2006) Factors Affecting Hospital Staff Judgments About Sickle Cell Disease Pain. Journal of Behavioral Medicine 29:2, 203

CrossRef

* Alexie Cintron, R. Sean Morrison. (2006) Pain and Ethnicity in the United States: A Systematic Review. Journal of Palliative Medicine 9:6, 1454

CrossRef

* John T. Chibnall, Raymond C. Tait, Elena M. Andresen, Nortin M. Hadler. (2006) Race Differences in Diagnosis and Surgery for Occupational Low Back Injuries. Spine 31:11, 1272

CrossRef

* K Sarah Hoehn. (2006) Family satisfaction from clinician statements or patient-provider concordance?*. Critical Care Medicine 34:6, 1836

CrossRef

* Joanne Lusher, James Elander, David Bevan, Paul Telfer, Bernice Burton. (2006) Analgesic Addiction and Pseudoaddiction in Painful Chronic Illness. The Clinical Journal of Pain 22:3, 316

CrossRef

* Sally G. Haskell, Alicia Heapy, M. Carrington Reid, Rebecca K. Papas, Robert D. Kerns. (2006) The Prevalence and Age-Related Characteristics of Pain in a Sample of Women Veterans Receiving Primary Care. Journal of Women s Health 15:7, 862

CrossRef

* Sandra H. Johnson. (2005) The Social, Professional, and Legal Framework for the Problem of Pain Management in Emergency Medicine. The Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics 33:4, 741–760

Summary Abstract and References Full Article PDF

* Michael W. Rabow, MD, and Suzanne L. Dibble, DNSc, RN. (2005) Ethnic Differences in Pain Among Outpatients with Terminal and End-Stage Chronic Illness. Pain Medicine 6:3, 235–241

Abstract Abstract and References Full Text Article Full Article PDF

* Mark A. Lumley, PhD, Alison M. Radcliffe, BA, Debra J. Macklem, MA, Angelia Mosley-Williams, MD, James C. C. Leisen, MD, Jennifer L. Huffman, PhD, Pamela J. D’Souza, PhD, Mazy E. Gillis, PhD, Tina M. Meyer, PhD, Christina A. Kraft, MA, and Lisa J. Rapport, PhD. (2005) Alexithymia and Pain in Three Chronic Pain Samples: Comparing Caucasians and African Americans. Pain Medicine 6:3, 251–261

Abstract Abstract and References Full Text Article Full Article PDF

* April Hazard Vallerand, PhD, RN, Susan Hasenau, MSN, RN, Thomas Templin, PhD, and Deborah Collins-Bohler, MSN, RN. (2005) Disparities Between Black and White Patients with Cancer Pain: The Effect of Perception of Control over Pain. Pain Medicine 6:3, 242–250

Abstract Abstract and References Full Text Article Full Article PDF

* Barry A. Eagel, MD, and Louis W. Sullivan, MD. (2005) Response to Letter to the Editor Re: Leveling the Playing Field. Pain Medicine 6:3, 271–272

Summary Abstract and References Full Text Article Full Article PDF

* Gabriel Tan, PhD, Mark P. Jensen, PhD, John Thornby, PhD, and Karen O. Anderson, PhD. (2005) Ethnicity, Control Appraisal, Coping, and Adjustment to Chronic Pain Among Black and White Americans. Pain Medicine 6:1, 18–28

Abstract Abstract and References Full Text Article Full Article PDF

* Robert R. Edwards, PhD, Mario Moric, PhD, Brenda Husfeldt, PhD, Asokumar Buvanendran, MD, and Olga Ivankovich, MD. (2005) Ethnic Similarities and Differences in the Chronic Pain Experience: A Comparison of African American, Hispanic, and White Patients. Pain Medicine 6:1, 88–98

Abstract Abstract and References Full Text Article Full Article PDF

* Linda S. Ruehlman, PhD, Paul Karoly, PhD, and Craig Newton, PhD. (2005) Comparing the Experiential and Psychosocial Dimensions of Chronic Pain in African Americans and Caucasians: Findings from a National Community Sample. Pain Medicine 6:1, 49–60

Abstract Abstract and References Full Text Article Full Article PDF

* Barbara A. Hastie, PhD, Joseph L. Riley, PhD, and Roger B. Fillingim, PhD. (2005) Ethnic Differences and Responses to Pain in Healthy Young Adults. Pain Medicine 6:1, 61–71

Abstract Abstract and References Full Text Article Full Article PDF

* Fadia T. Shaya, PhD, MPH, and Steven Blume, MS. (2005) Prescriptions for Cyclooxygenase-2 Inhibitors and Other Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Agents in a Medicaid Managed Care Population: African Americans Versus Caucasians. Pain Medicine 6:1, 11–17

Abstract Abstract and References Full Text Article Full Article PDF

* Carol S. Weisse, PhD, Kemoy K. Foster, B.S., and Elizabeth A. Fisher, B.S.. (2005) The Influence of Experimenter Gender and Race on Pain Reporting: Does Racial or Gender Concordance Matter?. Pain Medicine 6:1, 80–87

Abstract Abstract and References Full Text Article Full Article PDF

* Carmen R. Green, MD, Raymond C. Tait, P hD and Rollin M. Gallagher, MD, MPH. (2005) The Unequal Burden of Pain: Disparities and Differences. Pain Medicine 6:1, 1–2

Summary Abstract and References Full Text Article Full Article PDF

* Roger B. Fillingim. (2005) Individual differences in pain responses. Current Rheumatology Reports 7:5, 342

CrossRef

* Roxanne Garbez, Kathleen Puntillo. (2005) Acute Musculoskeletal Pain in the Emergency Department. AACN Clinical Issues Advanced Practice in Acute and Critical Care 16:3, 310???319

CrossRef

* Raymond C. Tait, John T. Chibnall. (2005) Racial and Ethnic Disparities in the Evaluation and Treatment of Pain: Psychological Perspectives.. Professional Psychology Research and Practice 36:6, 595

CrossRef

* Gary L. Stein, Patricia A. Sherman. (2005) Promoting Effective Social Work Policy in End-of-Life and Palliative Care. Journal of Palliative Medicine 8:6, 1271

CrossRef

* Scott M. Fishman, MD, Rollin M. Gallagher, MD, MPH, Daniel B. Carr, MD and Louis W. Sullivan, MD. (2004) The Case for Pain Medicine. Pain Medicine 5:3, 281–286

Abstract Abstract and References Full Text Article Full Article PDF

* ROLLIN M. GALLAGHER, MD, MPH,. (2003) Measuring Emotions in Pain: Challenges and Advances. Pain Medicine 4:3, 211–212

Summary Abstract and References Full Text Article Full Article PDF